Now live: a smarter way to manage, share and sign your company documents – with powerful AI integration on the horizon

As your company grows, so does your paperwork – new hire contracts, advisor agreements, pitch decks, investor updates an...

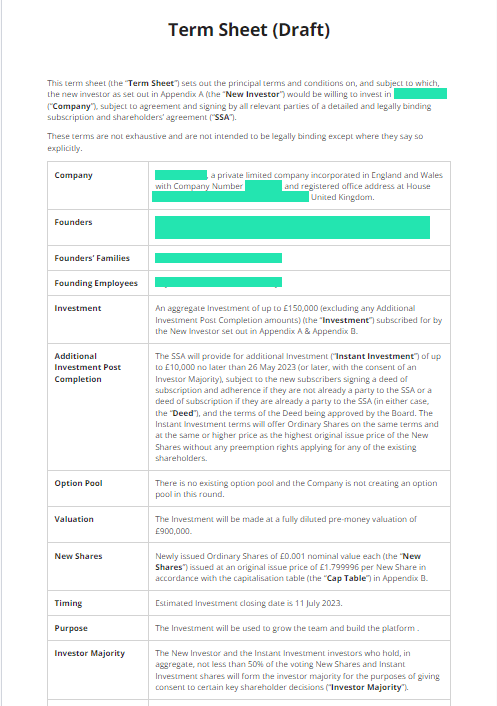

A Term Sheet is a non-legally binding agreement that summarises the key deal terms of the funding round. It’s one of the most important negotiation tools between founders and investors.

In this post, we explain the core deal terms you’ll see in a Term Sheet, and some general dos and don’ts to consider when building a Term Sheet for your investment round.

The Term Sheet serves as a summary of the more detailed investment agreements you’ll go on to lock down in the Shareholders Agreement and Articles of Association. Essentially, the Term Sheet functions like a Letter of Intent, and indicates that both parties are committed to the deal and the form it will take.

While it’s not a legally binding contract, all investors will typically agree and sign the Term Sheet first. That means the bulk of the negotiations take place before the legally binding documents are created.

The deal terms defined here can shift power in favour of either the investor or founder, so it’s important to strike the right balance at this stage of the negotiation. You’ll want to safeguard everyone’s interests but do so in a way that helps your round close quickly and efficiently. We’ve seen rounds stay open for months, with founders and investors haggling over some totally trivial deal term – that’s not the way to scale your business.

There’s a huge range of different directions deal terms can take. At SeedLegals, we’ve seen thousands negotiated and can tell you which terms and conditions are most common and what to be wary of.

✔ Build customised terms in a few clicks

✔ Create an expertly drafted document that’s ready to send

✔ Talk to us anytime - unlimited support at no extra cost

Ideally, you want to be the one to get your Term Sheet on the table first. VC firms will sometimes send their own Term Sheets to you. But, wherever possible, you should take the lead with potential investors and be clear about what key deal terms you’d like to see in exchange for equity.

There are three main benefits to sending your Term Sheet first:

To help you get ahead with your Term Sheet strategy, we’ve listed the most important negotiation points below.

With over 35,000 startups and 25,000 investors using SeedLegals, we have a unique view into the deals that are actually happening right now in the UK (and beyond). We’re in a position to let you know what’s market standard and what’s unconventional, unfair or unwise.

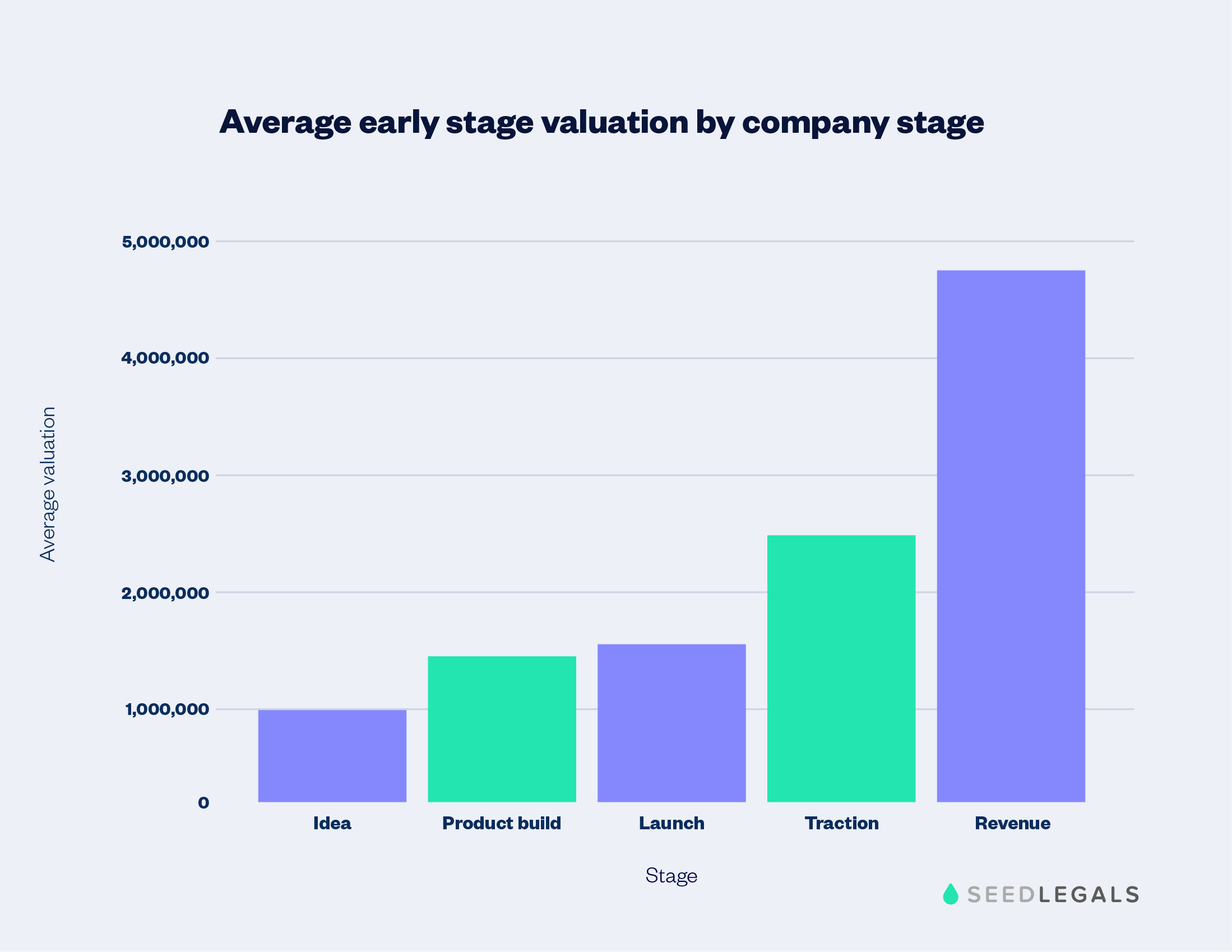

The company valuation is simply how much equity you’re giving away in exchange for the investment amount. The valuation of an early-stage company is more of an art than a science, especially when the company is pre-traction or pre-revenue and there aren’t any hard numbers to take into account.

At SeedLegals we’ve decoded the factors that underpin early-stage startup valuations and created a quick cheat sheet to help you see whether your valuation is in line with other UK companies at a similar stage of growth.

Our data shows that startups commonly give away 15% of equity in each round. Given that startups will usually raise enough to last the company for a 12-18 month runway, we can work out what a typical valuation is. Here’s our assessment of ‘normal’ valuation ranges depending on the stage of your startup.

Idea stage: £1M

Product build: £1.3M – £1.5M

Launched: £1.5M

Traction: £2M – £3M

Revenue: £2M-£3M

For more information on getting the balance right between equity and investment see How to value your startup and How to value a pre-revenue company.

The average valuation ranges above refer to pre-money valuations. It’s critical that you and your investors are on the same page about whether you’re talking about pre-money valuation or post-money valuation in your Term Sheet.

Whether you’re referring to a pre-money valuation or a post-money valuation can make a significant difference in the size of the equity stake your investors take away, because it affects the price per share.

At every funding round, existing shareholders are diluted because new shares have to be issued to give to new investors. This reduces the shareholder’s overall shareholding percentage.

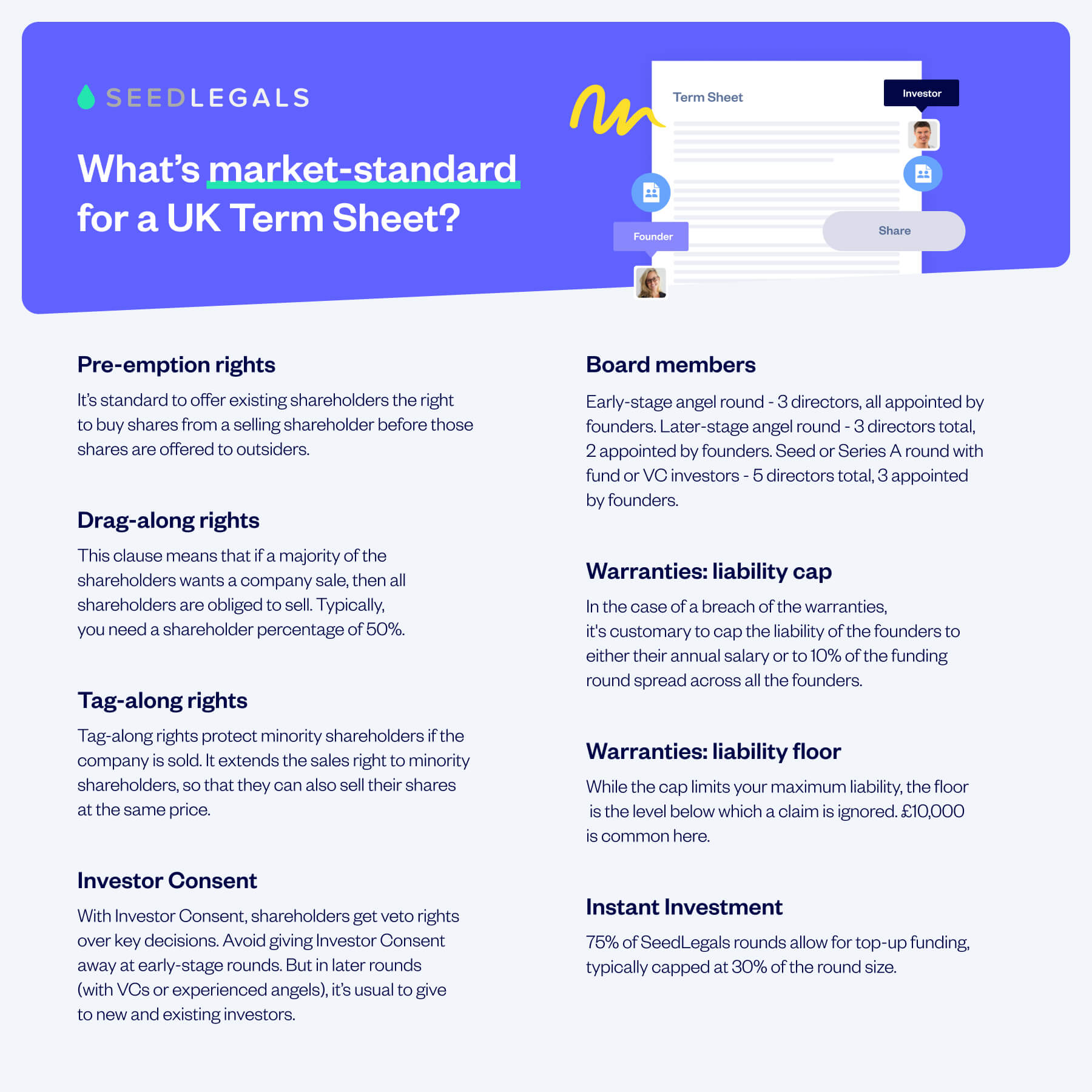

Pre-emption rights protect investors from being diluted. They give existing investors the right to buy additional shares before those shares are made available to new investors. Whether the investor has pre-emption rights or not is specified in the Term Sheet.

These rights come into play when selling the company becomes a possibility. The aim here is to balance the potentially competing interests of majority and minority shareholders.

Usually in early-stage companies, the investors are minority shareholders and the founders still own most of the equity.

Drag-along: If a certain percentage of shareholders want to go ahead with the sale of the company, then all shareholders must sell at that price.

The rationale behind this is that buyers will usually be looking to buy the company as a whole. Drag-along rights help the company in their dealings with potential buyers by ensuring it’s not held hostage by a few shareholders who refuse to sell.

Typically 50% of shareholders need to agree to invoke the drag along. So three quarters of shareholders who are eligible to vote must be on board to sell the business on behalf of all shareholders.

Tag-along: The tag-along clause protects minority shareholders if the company is being sold. In the event of an exit share sale by a majority shareholder, tag-along extends the sales right to other shareholders, so that they can also sell their shares at the same price as the majority shareholder if they want.

Investor Consent is one of the most hotly contested items on the Term Sheet.

Since founders are usually still the majority shareholders after early-stage funding rounds, they generally have free rein to run the company with little external control. However, since investors have put a large amount of money into the company, they often want some say over decisions that could impact the return on their investment. That’s where Investor Consent rights come in – they give investors the right to veto certain key decisions.

These decisions include payments and salaries over a certain amount and debts taken on by the company – but they can extend to almost all elements of the company’s business.

The Term Sheet specifies which group of investors have Investor Consent and what matters they have veto rights over.

Institutional investors will often ask for a board seat, known as an Investor Director position. Our data shows that founders end up giving Investor Director positions much more often than they initially planned to.

Founders need to decide whether or not to allocate investors a seat on the board. Your decision will depend on a number of factors, including whether the board is balanced in terms of shareholder representation and how the investor’s experience can add value to the board’s proceedings.

Remember that too many directors on the board can hamper an early-stage startup’s ability to make and action decisions quickly. Here’s our take on which investors to consider adding to your board:

After an angel round, investors will normally have a significant shareholding in the company, and they more often than not will be an ally of the founder. However, if a founder is only giving away a small amount of equity and the chosen director will not add a lot of value through their knowledge or experience, then it’s usually not worth giving them a board seat at this time.

Funds and venture capital funds invest larger amounts and typically demand a board seat. Because they have a duty of care over their investors’ money, they’re usually keen to minimise risk and maximise return on investment and therefore want more control over a company’s decisions.

This doesn’t have to be a bad thing by any means. Good VCs can bring valuable insights and experience to the board.

But remember that striking a deal with an investor is like getting married with no means of divorce. Founders need to do their homework and weigh their need for investment with the investor’s expectations. Generally, the more they put into the company, the higher their demands are going to be.

For more information, see Should your investors get a seat on the board?

Mostly the day-to-day running of the company is left to the CEO and executive team. For some decisions the board’s approval is needed. In very early-stage companies, usually only the founders are on the board so those matters just get approved by default.

If external directors are appointed to the board, the Term Sheet outlines which activities need board approval.

In company governance terms, board approval sits below investor consent. This means a situation could arise where items are approved by the board, but then vetoed by investors with investor consent rights.

There are two main types of shares in a startup: ordinary shares and preference shares. To put it simply, ordinary shares are – well – ordinary. They don’t get special treatment compared with other share types.

Preference shares are treated differently. The two main preferential rights they receive are liquidation preferences and anti-dilution.

A liquidation preference is all about what happens to the proceeds of a startup if there’s an exit sale or a winding up of the company.

If all shareholders own ordinary shares, the total amount raised from the sale is paid back equally to all shareholders, proportional to the number of shares they own.

However, if there are shareholders with preference shares, those investors get their money back first before the ordinary shareholders get paid – and sometimes even get twice or three times the amount they invested before any other shareholders see any proceeds.

Anti-dilution protects shareholders from being diluted by new funding rounds. The most common anti-dilution provisions come into play if the company raises at a lower valuation during their next funding round – this is called a ‘down round’.

Investors generally don’t like having their stake in the company reduced by new share issuances, especially if the new investors pay a lower price per share than they did. When a company does a down round, the value of an existing investor’s shareholding drops drastically. Not only does their shareholding percentage in the company decrease, the value of each share they hold falls.

The anti-dilution clause tops up the existing shareholder’s equity stake by compelling the company to issue additional shares to them. As this is quite an aggressive action, we generally don’t see this unless a major investor is involved in the round, or until much later-stage funding rounds.

For more information about why you should be wary about offering these types of shares, read our article on anti-dilution and non-dilution shares.

Founders often put their own money into their business in the early days, as a founder (or director) loan. This is money that can be repaid to the founder.

The Term Sheet lays out the conditions under which it will be repaid. There are several ways it can be repaid – for example, the loan can be converted into shares during the funding round or it can be paid out from the company’s free cash flow.

You can read more about this in our article on founder and director loans.

It can be difficult for a founder to convince an investor to repay their money, but because this money comes tax free, it makes sense for it to form part of the founder’s payments through the business.

Instant Investment allows you to raise additional funds to top up a funding round after it closes.

These additional investors sign onto the funding round deal terms, with no room for further negotiation. This means you can get funds in immediately and not wait until all investors are lined up for your next round.

Most founders on SeedLegals choose to enable this in the Term Sheet to allow them flexibility with their fundraising going forward. You’ll need to negotiate with investors the total amount you can raise this way, and for how long after the round closes you can top up using Instant Investment.

Read more about the continuous funding model and Instant Investment.

Aleena MuhammadWe recommend you enable Instant Investment in your funding round, as you’re basically buying the flexibility to top up your round in the future and getting all of the necessary approvals upfront. You can always arrange to use Instant Investment afterwards regardless, but why not give yourself the flexibility now?

Funding Team Lead,

Instant Investment is one of those rare circumstances in which you wouldn’t build pre-emption rights into the provisions. This gives you the flexibility to raise quickly, without having to go back to your investors frequently.

Investors commit money based on promises about the health and viability of the company – for example, that the cap table is correct, the company isn’t being sued and that it owns its intellectual property.

There can be severe financial penalties if a founder misrepresents their company or fails to disclose something that might affect an investor’s willingness to invest.

A cap is usually set per founder which basically outlines how much they would personally be liable for. It’s customary to cap the liability of the founders to 1x their annual salary – though if the founder isn’t being paid anything yet, then a fixed figure comes in. On SeedLegals, this is normally around £20,000.

A floor is the opposite of a cap. While the cap limits your maximum liability, the floor is the level below which a claim is ignored. For example, if the floor is set to £10,000 and the investors want to make a claim against the company for £5,000, it would be considered too small to bother with, and dropped.

On SeedLegals, it’s quick and easy to build a Term Sheet template with founder-friendly provisions. We’ll let you know what’s industry-standard, what you can consider compromising on and what to push back on.

Simply answer the questions and we generate a Term Sheet that’s ready to share with your investors. You can either choose our regular, long-form format, or you might prefer the mini version which lists just the main deal terms. It’s about 30% shorter.

The SeedLegals live commenting feature makes it simple for you and your investors to get on the same page. With commenting, you no longer need to download a document and send it back and forth with tracked changes – you can keep track of your negotiations alongside your terms in SeedLegals.

After you and your investors have come to an agreement, you’ll both sign the Term Sheet.

But before they’ll sign the legally binding contracts or part with any money, they’ll conduct extensive due diligence on your company.

VC investors in particular will have an extensive checklist for their due diligence covering many aspects of your business – from tax, finance and legal to your IT, sales and marketing systems and statistics.

A digital data room can help speed this process along. It allows you to store all the sensitive documents in one place, control access and update everything in real time.

After the investor is satisfied with the health of your company, it’s time to create the official legal contracts for the round. These include:

For a full explanation of every stage of an investment round, see this step-by-step guide to a funding round.

See the latest insights from our funding experts and learn how to take cash quickly with agile funding tools.

Download free ebookHas an investor sent you a Term Sheet full of clauses you don’t understand? Or are you stuck on what deal terms you need for your round? We’re here to help.

Watch SeedLegals co-founder and CEO Anthony Rose pick apart a Term Sheet in this Term Sheet clinic video. Or choose a time using the form below to talk directly to one of our funding specialists.