SeedLegals Termometer, the definitive guide to UK funding round deal terms

Welcome to SeedLegals Termometer, the world’s most detailed analysis of early-stage funding round deal terms.

Using data from 2000+ funding rounds done on SeedLegals, we analysed each of the key terms that founders and investors negotiate in funding rounds done on SeedLegals. We then grouped those into Small (under £200K), Medium (raising £200K to £700K) and Large (£700K to £10M+) rounds. We then created histograms for each deal term, for each round size, to show you what’s market standard for your round.

And, we added commentary to explain what each term means, what the data shows, and what this means for you.

Whether you’re a founder setting up your round, an investor who’s received a term sheet, or a lawyer being asked to review funding round deal documents, Termometer data is an essential resource to help you get the right deal for your stage company and for your investment.

We first created this Termometer in 2019. Recently we did an audit of the data in this article and saw that when we compared the data of the past 12 months, we saw consistency with the data that we compiled in 2019. The largest variation that we have seen is, understandably, in valuations. However, the fact that there has been such uniformity in rounds in the last 6 years shows that investors are, generally speaking, looking for the same key deal terms as they were 6 years ago.

Valuation

‘What valuation should I set for my round?’ is always a complicated question.

First of all, there are several different methodologies of calculating a valuation for a company. These include:

- Market Capitalisation

- Discounted Cash Flow

- Earning Multiplayer

Just to mention a few. However, the problem that most startups face is they are either pre-revenue or in the early revenue generating stage. This means they lack the financial data to calculate a quantitative valuation. This means the valuation often comes down to qualitative aspects of the business such as the founding team’s experience and expertise, the product, vision and narrative and the network and advisors that the company has. However, justifying a valuation that is based on qualitative aspects to investors can be tricky. If this is an area that you need assistance with, please reach out to your account manager regarding our Blox partnership.

It’s always worth bearing in mind that the valuation of the company is not just ‘what the company is worth’. It is also a mechanic by which equity is given to investors. Therefore, a valuation can be reversed engineered by first working out what level of investment is needed, and how much equity you are looking to give away in return for the investment. Once you have these bits of information, the following equations can be used to calculate your round valuation.

Investment x Equity Given Away = Post-Money Valuation

Post-Money Valuation – Investment = Pre-Money Valuation

When using this approach it can be useful to forecast your next 3-4 fundraises and roughly work out how much equity you want to hold by the time these fundraises have taken place. From here you can work backwards, to calculate that by Round 4, you will need to give away X amount of equity, Round 3 you will need to give away Y amount of equity etc.

What the data shows

In the past 12 months the mean valuation for companies doing their first funding round on the platform was £2.89 million. The total range that we saw for the average valuations for funding rounds were between £1.4 million and £5 million.

For subsequent rounds on the platform i.e. data from companies who were doing their 2nd, 3rd, 4th etc, the mean valuation was £7.33 million. Here, there is a much larger range from £2.68 million to £16.2 million.

Instant Investment

Enable instant investment top up after the round has closed?

In the past when you did a funding round, once the round was closed adding investment later meant doing another round. But that’s all changed, more than 70% of all investment raised on SeedLegals is now outside a funding round. We call it agile fundraising.

By enabling Instant Investment in your round we build the permission to issue more shares into your funding round documents so you can top up later, at the same time, or at a higher valuation, without needing your shareholders’ permission (although you may have to offer the shares to them first), making it easier to top up as you find additional investors.

What the data shows

Founders have enabled the Instant Investment / rolling close provision in around 75% of funding rounds, allowing them to top up later.

Instant Investment gets used a bit more in smaller rounds than larger ones which reflects, in part, that some founders are intentionally doing smaller funding rounds to raise sooner, and then including a large Instant Investment topup provision so they can ‘complete’ the round later.

What this means for you

Unless an investor pushes back on it, or you’re certain you don’t plan to raise again ahead of your next round, you may as well enable this in your round, there’s no cost or downside for doing so, and it could save you a lot of admin overhead later.

What is the maximum allowable additional investment amount?

When you enable Instant Investment in your round, how much top up should you allow for?

What the data shows

The chart above shows just the most common amounts that are specified. It’s apparent that the larger the amount being raised, the larger the Instant Investment topup that founders want to include.

What this means for you

Setting the Instant Investment top-up amount to 30% of the round size looks to be a common pattern, allowing you to top up that amount more later with no additional permissions needed, at the same or higher valuation as the funding round.

Will existing shareholders have a preemption right on the additional investments?

When you enable Instant Investment in your round, you can configure it so that no additional permissions are needed to raise more until the specified limits have been reached.

In general when you issue new shares, existing shareholders will have a preemption right – that means they have the right to invest more to keep their existing percent equity and avoid being diluted. Having to offer preemption each time you issue new shares is an admin overhead – shareholders typically have 14 days to take up that right if they want to… so we also allow you to get their waiver in relation to the additional investment up front, allowing you to keep topping up without needing to go through the preemption process again.

What the data shows

Around 75% of the time, founders select that no preemption will be offered to existing shareholders, allowing for the least admin overhead topping up later.

What this means for you

Investors will usually – but not always – agree to give up their preemption rights on the Instant Investment amounts if those amounts are modest. For example, if you’re raising £500K in a funding round and allowing for up to £200K in top-ups later, it usually won’t bother investors that they’ll be diluted later, with no automatic preemption right. But, if you’re planning on allowing for up to £500K in Instant Investment top-up, that’s quite a lot of potential additional dilution later, so in that case investors may well want a preemption right.

Our suggestion is to specify no preemption right on Instant Investment topups, and only enable it if investors ask for it.

SEIS/EIS Advance Assurance

Have you applied for SEIS/EIS Advance Assurance?

If you’re offering SEIS or EIS tax benefits to your investors they’ll be keen that you have Advance Assurance. There’s no legal requirement to have Advance Assurance but many investors will require it before they’ll invest.

What the data shows

The data shows how important SEIS and EIS is for UK funding rounds, with 85% of companies either getting SEIS/EIS Advance Assurance ahead of starting their round on SeedLegals, or intending to do that.

What this means for you

This is clearly something that investors inspect, and being able to say “yes, we have our Advance Assurance” is often the difference between an investor saying “I’m in” vs. “Call me when you have your Advance Assurance”.

Preemption

Instant Investment aside, who has the right to be offered shares in future funding rounds?

Preemption gives shareholders the right to buy more shares later so that they can maintain their percent equity stake in the company.

Here, you’re specifying which shareholders will have a preemption right in future – you can choose whether it’s all shareholders, or only voting shareholders, or only the new investors in this round, or specific share classes.

What the data shows

The data shows that the most popular choice is that preemption is only offered to holders of voting shares. This matches the usual practice on crowdfunding platforms, the idea being that small investors get non-voting shares, and then you save yourself a lot of admin overhead later by only having to contact the smaller number of shareholders who have voting shares, to offer them their preemption right.

What this means for you

If you are planning on having lots of smaller investors with non-voting shares then our suggestion is to enable preemption for the holders of voting shares only, which will save admin overhead later.

Additionally, if you’re planning to create an EMI Option Scheme for employees, by only giving preemption to holders of voting shares and giving non-voting shares to your employees will help get a better EMI valuation discount for your employees’ share options.

Who gets the right to purchase shares from another shareholder before they are offered to the outside market?

Generally existing shareholders are given the opportunity to buy shares from a selling shareholder before those shares are offered to outsiders, known as Preemption on Transfer or Right of First Refusal. Here, you can specify what you’d like for your company.

What the data shows

The most common selection is that when a shareholder wants to sell their shares, they need to offer their shares to all existing shareholders before they can sell them to their intended buyer. By giving existing shareholders the first right to buy shares from a selling shareholder, you avoid scenarios where someone could sell their shares to a competitor, or someone you don’t like, at least not without your shareholders having the opportunity to buy those shares first, on the same terms.

What this means for you

If you plan to have many small shareholders with non-voting shares, then we recommend that preemption is offered to holders of voting shares only.

Drag, Tag & Co-Sale

Drag Along

Drag Along means that in the event of an offer to buy the company, if a majority of the shareholders want to go ahead then all shareholders are obliged to sell. If you don’t have this provision you can be stonewalled or blackmailed by a few holdout shareholders.

What the data shows

Drag Along is an incredibly important provision for founders to include in funding round documents. And, it’s also something that investors will generally insist on. So, with very few exceptions, Drag Along will almost always be enabled in a funding round – in fact the only reason we provide this question at all, is so founders and investors can see at a glance that Drag Along is enabled just by looking at the Key Terms selections.

What this means for you

If you’re planning on having many small shareholders with non-voting shares, then giving Drag Along rights to just the holders of voting shares saves needing to contact those smaller investors when a Drag Along vote is needed.

Drag Along percent

The Drag Along percent specifies the % of shareholders, by the number of (typically) voting shares held by them, that, were they to agree to a sale of the company (once there’s a potential buyer), could then force all shareholders to have to sell their shares.

Drag Along is therefore an extremely important provision to have – it avoids a few renegade shareholders blocking the sale of the company – but picking the right threshold is critical:

- Pick a threshold that’s too high and it may be difficult to reach the threshold and be able to sell the company,

- Pick a threshold that’s too low and the investors could force a sale of the company even if the founders don’t want to sell.

In early stage funding rounds the founders usually have 70% or more of the equity, so in these early days of the company there’s no chance of the investors being able to force a sale of the company, and the Drag Along discussion becomes whether the investors have any say at all in the sale of the company.

For example, if the founders have 75% of the shares, and the Drag Along percentage is set to 70%, that means the founders alone can force a sale of the company (notwithstanding any Investor Consent provisions). However, if the Drag Along percentage is 80%, the founders would require the consent of other shareholders, in addition to themselves.

But when a company gets to Series B or later, the tables are turned, and the founders may collectively have less than 50% of the equity. If the founders have less than 50% equity and the Drag Along percent is set to 50%, this means the investors can get together and force the founders to sell the business – perhaps to a buyer found by the investors, or even to one of the investors.

Note that in the discussion above we’re assuming that the founders are acting together… but that’s not always the case, founders often fall out, and then you may have scenarios where the investors side with one of the founders, against the other…

Note: we now recommend a Drag Along percentage of 50%, in line with the newer BVCA standard

What the data shows

The SeedLegals default used to be 75%, which is reflected in the table above. In 2023, the BVCA updated their model documents for early-stage investment, setting their recommended Drag Along percentage at 50%. We’ve now updated our advice to align the new BVCA standard of 50%.

What this means for you

We suggest picking a Drag Along percent that’s a little lower than the founders’ collective shareholding, so that the founders are able to negotiate a sale of the company, were they to find a buyer, and then force all the investors to sell too.

Occasionally there’ll be investors who ask for a higher Drag Along percent so that investors get a say on this, but we think those investor consents are dealt with in the Investor Consent provisions, and we would suggest showing investors that their protections exist there, not here (assuming that Investor Consent is enabled in your round).

Lastly, note that the Drag Along percent can be changed in your next round, so think about it as “what’s best between now and our next round”, rather than “what’s best forever”.

Tag Along

Tag Along means that if some shareholders want to sell their shares to a purchaser who is acquiring company, then all shareholders have the right to sell their shares on the same deal terms. This protects small shareholders from being taken advantage of by founders or larger investors colluding to sell the company, and so it’s a provision that all investors will usually be expecting to see.

What the data shows

Tag Along is almost universally enabled and, like Drag Along, really the only reason we make it an option on SeedLegals is so that founders and investors can see at a glance that this has been thought about and is enabled, simply by looking at the Key Terms summary.

What this means for you

With rare exception, you’ll want to enable Tag Along in your round.

Co-Sale

A Co-Sale right means that if the founders (and in some cases shareholders too, see below) wish to sell their shares, other shareholders will have a right to sell a pro rata proportion of their own shares too.

The co-sale right exists to protect investors from the founders deciding to sell out of the business – the idea is that the investors invested in the founder, so the investors don’t want to be in the position that the founders cash out and the investors are left with a company, but without the founders who they invested in.

By giving investors the right to sell a proportion of their shares to match the % of shares that the founders sell, the co-sale right means that if the investors don’t have faith in the business as a result of the founders selling out, the investors can sell out a proportion of their shares too.

The side effect of the co-sale right is that it makes it harder for the founders to sell their shares – they can’t simply find a buyer and sell some shares to them, instead, having found a buyer, they now need to notify all shareholders of their intention to sell and allow the other shareholders to take up some of that offer… which can mean the founders are then able to sell fewer shares themselves to that buyer.

See SeedLegals lets founders sell some of their shares at any time, pay only 10% CGT

What the data shows

If the vast majority of cases Co-Sale rights are enabled in a round, reflecting the SeedLegals default.

What this means for you

Co-sale rights are an investor protection, it adds friction to founders sell their shares. So as a founder it’s tempting to want to turn off that feature. But, our recommendation is to leave it enabled, both because many investors will be looking for this protection.

Do the Co-Sale provisions apply only to founders or to shareholders too?

As explained above, co-sale rights are generally there to protect investors from founders selling out of the business, it gives investors the right to sell a corresponding % of their shares on the same terms.

But co-sale rights could equally be used to protect founders, or other investors, from a (typically) major investor selling out. By making the co-sale right apply not just to founders but to all shareholders, it means anyone selling their shares would have to allow others to sell the corresponding % of their shares, on the same terms.

Making co-sale rights apply to all shareholders is going to make the company more like a family… once you’re in, it’s harder for anyone to leave.

What the data shows

The vast majority of funding rounds, correctly, have co-sale rights apply to founders only.

But for some later-stage rounds where a major investor could have similar numbers of shares to any of the founders, co-sale rights are sometimes specified as applying to all shareholders.

What this means for you

If co-sale rights applied to every shareholder then anytime anyone sells shares, that co-sale right would need to be offered to every other shareholder, making every share sale an unwieldy exercise. So in early stage rounds it makes sense that co-sale rights apply to the founders only. But where other shareholders have significant percentages of the company you might want to extend co-sale to them too.

Investor Consent

Investor Consent enabled?

By law, some company actions (like issuing new preferred shares) need shareholder approval – as in, approval by the majority of the shareholders.

In the early stages of a company the founders own the majority of the shares, so they could simply vote, by themselves, to do anything they want. To avoid that, the concept of Investor Consent (also known as Reserved Matters) was created so that some actions, separate from needing the approval of a shareholder majority, also need the consent of the investors (as in, excluding the founders).

Investor Consent is often one of the most difficult points in a funding round for founders to accept – it can create significant tensions between the founders and investors later on, with the potential for investors to prevent the company being sold later, or doing a new funding round at a valuation the investors don’t agree with, or entering new markets, or pivoting to a new product proposition.

In this question, you can choose whether Investor Consent will be needed at all, and if so, who will be included in the Investor Consent vote.

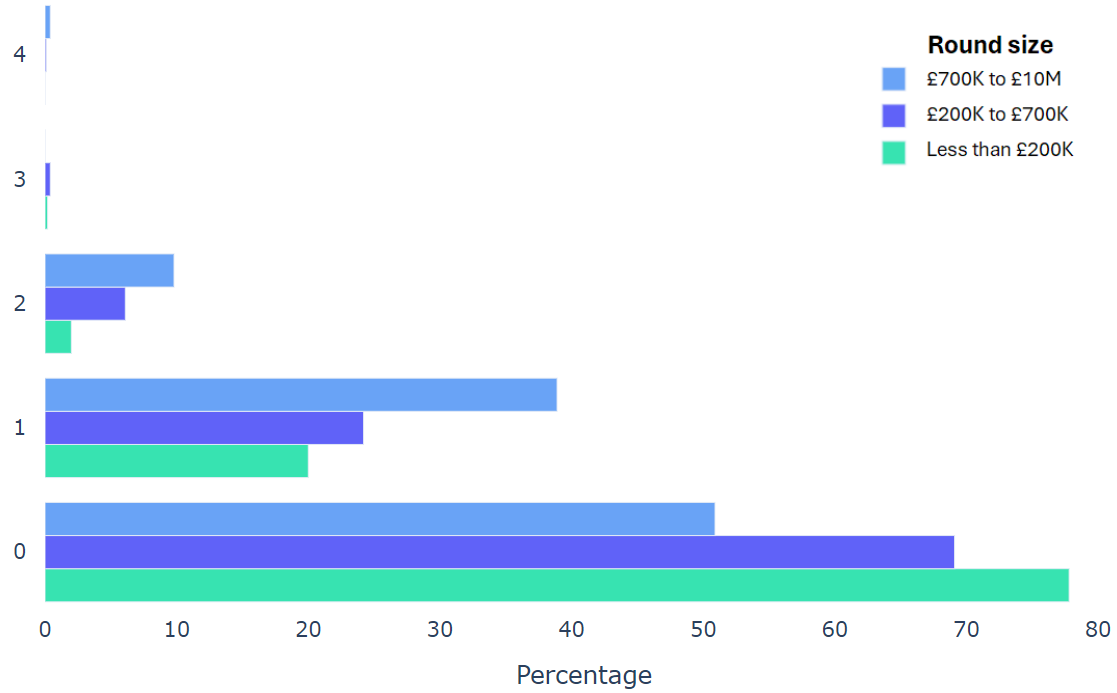

What the data shows

The data makes it clear that in early stage funding rounds, in the majority cases there is no investor consent. But when you get to Series A, it’s unlikely that your investors won’t insist on Investor Consent, and there’s little point trying to fight it.

After an early stage funding round the founders generally have free rein to run the company with little external control. But in later stage rounds investors usually ask for Investor Consent on the payment of dividends, changing the number of directors, etc., so they get a say on those matters.

One of the interesting nuances is, if there is investor consent, deciding which investors will get that consent – will it be just the investors in your latest funding round, or previous investors too?

There’s no obvious right or wrong answer to that, but in general you want to avoid later-stage VC investors stomping on the rights of earlier angel investors, without whom you’d never have gotten to this stage. So in general we’d recommend that Investor Consent includes all investors, not just the ones in your latest round.

However, if your last round raised £200K and your next round is raising £2M, your investors in the next round might argue that they alone should have the Investor Consent rights, as they put in 10X the amount of money as the previous investors.

An alternative to “new investors” vs. “new and existing investors” is giving the Investor Consent right to holders of a specific share class, and you can then allocate that share class to particular investors. For example, you might say that anyone who invests over £100K gets A Ordinary shares. Then, by giving Investor Consent to the A Ordinary shareholders, you’re only needing to get agreement from a few key investors later (which BTW may turn out to be less good because it concentrates power with them).

What this means for you

We think the above chart is one of the most helpful of all the SeedLegals Termometer data, helping both founders and investors understand what is market standard at different stage funding rounds.

The key take-away point is that if you’re raising £200K or thereabouts, you should push for no investor consent, noting that SEIS/EIS funds, VCs, and some angel investors may insist on it). However, if you’re raising a Series A round, it’s unlikely there won’t be an Investor Consent requirement.

Investor Consent means what % of those investors, by number of shares held?

If you have Investor Consent provisions in your round, then the next question is, what % (by number of voting shares held by the relevant investors) is needed to reach that investor consent majority?

What the data shows

The data makes it clear that that 50% is standard.

Just occasionally you may have investors asking for a larger majority being needed – in some cases that’s something to push back on, in other cases it might simply be a result of there being, say, 4 equal investors, and they deciding that the consent of any three of them is needed, and so they may propose, say, 65% as the Investor Majority percent.

What this means for you

We suggest staying with 50% unless there’s a good reason for something different.

More importantly, take care to avoid any one investor being able to block consent matters, unless of course there is one investor who overall has more than 50% of all investor shares, in which case they will hold the cards regardless.

Investor Director Consent

As the CEO of the company you can usually happily buy a new espresso machine for the office without needing anyone’s permission. And your board is perfectly capable of making the decision about hiring someone for a £200K per year salary, or opening a subsidiary company in Australia, or creating a share option scheme.

But what if your investors appointed an Investor Director and want that director to have a say on some board-level matters?

There’s a list of around 20 things that, in some combination, usually get included as things that the board can only action with the Investor Director’s approval – you’ll see those listed in a Schedule of the Shareholders Agreement.

Rather than forcing you to think through every combination of those 20 or so common approval items, we packaged them into two choices: Lite and Full, with the option to customize them further as needed.

What the data shows

In the vast majority of early stage round, the smaller (“Lite”) set of approvals is chosen, with that only dropping slightly in later stage rounds.

What this means for you

Our suggestion is to start with the Lite selection and, if the investors ask for additional approvals, you can add those as agreed as Custom additions.

You Snooze, You Lose

You Snooze, You Lose enabled?

If Investor Consent is enabled then some decisions, like issuing new shares, will require you write to your investors to get their consent. But what if you can’t get hold of an investor or they don’t respond? That’s where You Snooze, You Lose comes in: any investor who fails to respond within 15 business days is deemed to have given consent.

Enabling this also avoids delays while you try to get responses from tardy or unreachable shareholders for approval to vary the Shareholders Agreement, which you’ll need at your next funding round.

What the data shows

You Snooze, You Lose is a new concept, unique to SeedLegals.

Angel investors will likely be happy, VCs and funds may push back on it.

We’re delighted that You Snooze, You Lose is enabled in 65% of rounds.

What this means for you

You Snooze, You Lose is one of many advantages to using SeedLegals for your round – we know what goes wrong in funding rounds and we enhance our legal documents to predict and avoid those issue. Lawyers don’t think this way, you won’t find them adding this wording to your round.

You’ll definitely want to enable this feature – we’ve seen it save founders when investors or other shareholders go AWOL and refuse to respond to requests to sign approval documents. In some cases investors will push back, but do try.

Board Meetings

Board Approvals

How many board meetings per year are you committing to?

When you do a funding round you’re committing to your investors to hold periodic board meetings. But board meetings are an admin overhead – most founders would rather be working on product or sales than preparing board meetings, so the question is, how many board meetings a year should you commit to?

What the data shows

The data shows that the market standard is quarterly board meetings.

What this means for you

If investors ask for monthly board meetings show them this chart, explain that it takes 1-2 days to prepare the board pack, you’ll be slowing your development if you have to do that monthly. If the investor insists, try to quarterly board meetings with a short monthly KPI / revenue update in between.

Who is eligible to be appointed chair of the board?

Many founders don’t understand the role of the board chairperson, they think it’s some kind of advisor, someone you hire to look good on the pitch deck. But actually the chair’s role is very different. While the chairperson tends to be one of the directors – and just like the other directors, they have legal obligations as a director to act in the best interests of the company – they are also responsible for ensuring the orderly proceedings at the meeting and to prepare an accurate set of minutes of the meeting afterwards.

Additionally, in the event of an even number of votes for and against on a board resolution, the chairperson can have the casting vote (you can choose to have that, or not, when you set up your round on SeedLegals – see below). If the chair has a casting vote, that gives them even more power. So you’ll want to choose the chairperson wisely.

At SeedLegals we’re keen to help founders understand the function of the board and design their board so it will work for them, not against them, particularly if things don’t go to plan later on. Which is why we build into the funding round documents the ability to specify who can be appointed chair of the board, with a default that the chair will be appointed by one of the founders.

What the data shows

The data shows that most times companies go with the SeedLegals suggested choice, which is that the chair is appointed by the founders. In later-stage rounds that changes, first so that the chair is increasingly selected by the board collectively (so the investors have a say), and in a small number of rounds that the chair is appointed by the investors, or by the lead investor.

What this means for you

We recommend that, so long as the founders get on with each other, that the founders aim for a founder-led board, which means that the founders outnumber the investors on the board, or at least equal the number of NEDs and investors directors on the board, and that the chairperson is appointed by the founders. In some cases you may not be able to push back on an investor request that they be the chair… if you do get that request you may wish to remind the investors of all the onerous tasks that the chairperson needs to take on, some of which are covered here, and hopefully that will help them understand they really didn’t want that role.

Who chooses the chairperson?

Having decided who is eligible for being appointed as a chair of your board, as described above, you may then come up with one or more candidates for that position.

If there is more than one candidate, then the next question is who gets to vote to pick amongst those candidates.

What the data shows

The most common scenario is that the board as a whole votes to pick the chair from amongst the available candidates. For example, if there are two founders with equal numbers of shares, and they both wish to be chair, then the board as a whole will vote amongst them. And, in case you’re wondering what happens if there are equal numbers of votes for each how you’ll ever escape that Catch-22 gridlock, the answer is that at the time you set up your funding round, you’ll have the opportunity to specify who the first chairperson will be.

What this means for you

Generally you’ll go with the “board majority chooses the chair”, from the small list of possible candidates per the previous question above.

Directors & Observers

What is the maximum number of directors?

Here’s a rough guide to how companies often set up their board:

Early-stage angel round:

3 directors total, all appointed by the founders.

Angel round with investors who want more company oversight:

3 directors total, of which 2 appointed by the founders and 1 Independent Director (NED) or Investor Director appointed by the investors.

Seed or Series A round with fund or VC investors:

5 directors total, of which 3 appointed by the founders and up to 2 Independent Directors (NEDs) or Investor Directors appointed by the investors.

If you’re planning to allow for Instant Investment top-up later, leave enough room here to appoint any additional directors that later investors might want.

How many of those directors are the founders entitled to appoint?

These board positions will be reserved for the founders themselves or people who they choose (if there are more Founder Director positions than founders).

How many independent directors would you like?

These board positions are for Independent Directors, who are directors typically appointed by the board itself, and they tend to be the candidates who are acceptable to founders and investors alike. These can be Non-Executive Directors (NEDs) whose job is to bring an independent voice to the board. Independent Directors will have a vote on the board just like any other director, but won’t have any special veto powers beyond that.

How many investor directors would you like?

Investor Directors tend to be the investors’s voice on your board. Decisions which would otherwise have needed a burdensome shareholder vote can instead be made with Investor Director Consent. Investor Directors by default get an investor director consent right (you can fine-tune this in Advanced Terms), which means they have a veto right over some company decisions – those decisions are listed in a Schedule of the Shareholders Agreement.

If several investors are asking for Investor Director positions you might instead offer them Observer positions, see below, to keep your board lean.

How many observers would you like?

If several of your investors want a board seat and you don’t want to be in a position where the founders can be outvoted by the investors, you can make some of the board positions Observer roles. That means they’re not a Director and can’t vote, but they can sit in on board meetings and, well, observe.

If you’re planning to allow for Instant Investment top-up later, leave enough room here to appoint any additional observers that investors coming in later might want.

Investor Updates

Who will you provide investor updates to?

Your investors are going to expect periodic updates that include details on company performance, business plan updates, financial information, etc.

These would normally be expected by the new investors in this round, but you can specify that existing investors or all shareholders will get sent investor updates too.

What the data shows

In the company’s first funding round there aren’t any existing investors, so it’s only the new investors in the round that investor updates will be promised to (the founders not needing any updates themselves, of course).

But, starting the second funding round onwards, there are now existing investors too, and they now get included.

What this means for you

Investors value periodic updates from companies they’ve invested in. In fact it’s a common complaint amongst investors that founders promise periodic updates, but the only time they hear from them is when they need more money. Since it’s no more effort to share updates with everyone, our suggestion is that updates get sent to both new and existing investors.

How often will you provide investor updates?

Doing this monthly sets a good routine and helps keep your investors engaged. But that can be onerous, so quarterly is more typical.

What the data shows

The data shows that most times people go with the SeedLegals suggestion of quarterly.

What this means for you

Aim for quarterly updates, that’s probably about the right frequency. If investors ask for monthly updates, explain how much time and effort those updates take, time you could be spending on the product and team. If they insist, ask if quarterly updates are okay, with simple key metrics updates each month in between.

In a few cases founders get away with no promise of investor updates at all, which is nice, but best to keep your investors updated periodically, even if there’s no commitment to do so.

Founder Share Vesting

Will the founders' shares be subject to (reverse-)vesting?

To avoid the founders taking the money and retiring, investors usually require that founders ‘reverse vest’ their shares over a number of years. If a founder leaves during the vesting period they need to transfer back the unvested shares. Even if their shares are fully vested before the round, investors will often ask for a new vesting schedule to dissuade the founders from leaving right after their investment. If you need to justify to your investors why vesting should not start again you would explain that e.g. your shares were earned in exchange for years of work at no salary, etc. See how vesting also protects founders from themselves, and see our statistics on salaries and vesting.

When did vesting start?

If the founders previously signed a Founder Agreement then their shares will likely have begun vesting at that time. Or, if the investors want share vesting to start (or restart) now, then select the date of completion of this round.

What is the overall vesting period?

The founders’ shares (those that have not already vested) will vest in equal amounts over this period.

Investors will often ask for 4 year vesting and a 1 year cliff, founders usually push for 3 years and no cliff.

What percent of the founders' shares have already vested at the vesting start date?

If some fraction of the founders’ shares have already vested, you can specify that here.

What is the cliff period, in months?

The cliff is the time until the first set of shares vest. If some shares are already vested at the vesting start date, then no more will vest until the end of the cliff. At the end of the cliff, any shares that would have vested during the cliff period will immediately vest at that point.

At what frequency will the shares vest?

Will the founder's shares have accelerated vesting on a sale of the company?

This is known as Accelerated Vesting, it allows the founders to not have to wait out the entire remaining vesting period working for a new owner of the business, usually on the condition that the founders commit to staying on for some agreed period.

Leavers

Bad Leavers lose which shares?

A Bad Leaver is someone who is fired for fraud, gross negligence or gross misconduct.

If a founder is fired for that, should they lose all their shares, even ones that have already vested? Or only lose their unvested shares? Losing shares that have already vested is harsh, but some companies think that’s the right thing to do if a founder is a bad leaver.

At what price will a Bad Leaver have to transfer their vested shares?

The nil value is, well, zero.

The fair value is the price that the shares could be sold at today, as determined by an expert valuer. Be aware that the company could obtain a valuation that sets the fair value as close to zero, so fair value is often not as fair as one might expect.

When do Bad Leaver provisions apply?

Imagine that a founder or employee is fired for gross misconduct 5 years from now, well after all their shares have vested. Should they still lose all their shares? You can specify here whether the Bad Leaver provisions finish at the end of a person’s share vesting period, or continue for the duration that the founder or employee remains with the company.

Good Leavers

A Good Leaver is someone who leaves because of death, accident or disability, excluding voluntary departure.

If a founder dies or has an accident that leaves them unable to work, it would be gracious to let them or their family keep their vested shares. But having a big slice of the company’s equity locked up and non-productive is a barrier to future funding rounds. So a Good Leaver is usually allowed to keep their vested shares, but forced to transfer their unvested shares for fair value.

Forced Leavers

A Forced Leaver is a founder or employee who’s forced out of the company, perhaps because they were under-performing or by the new owners on a sale of the company.

Founder fallouts are surprisingly common, the company being able to reclaim at least the unvested shares helps minimise the damage if one of the founders needs to be terminated.

The fair value is the price that the shares could be sold at, as determined by an expert valuer. Note that the company could obtain a fair value valuation that is close to zero (a founder is leaving, limited remaining cash, etc.) so be aware that the fair value can be manipulated to be lower than you might expect.

Voluntary Leavers

A Voluntary Leaver is a founder or employee who leaves because they got bored or found another job.

The general expectation is that if you leave the company by choice you lose your unvested shares, but your vested shares are yours. But that may not be acceptable to investors and could make the next funding round more difficult, so a compromise is that a founder leaving during the vesting period only keeps their vested shares with board approval, otherwise they need to sell them at fair value.

Or, for an extreme Stay Or Lose, you can specify that if someone voluntarily leaves anytime during the vesting period they lose both their unvested and their vested shares.

If a founder has to give up unvested shares, what happens to those shares?

If a founder leaves the company and they’re obliged to give up their shares, those are usually offered to all shareholders. But, to allow the founders to preserve their shareholding in the company, you can instead specify that other founders have the first right to buy back those shares. If the other founders don’t take up that right, for example if the shares are being sold at Fair Value and the other founders don’t have the money to buy them, then they would be offered to all shareholders.

An alternative is to turn unvested shares into deferred shares of very little value. Only unvested shares that would otherwise have to be sold at nil value will be turned into deferred shares, any that are to be sold at Fair Value will be offered to other shareholders. To a company on SeedLegals’ documents this option will always be available, but you can make it the primary option.

If a founder leaves, will their shares continue to have voting rights?

If a founder leaves the company they generally keep their vested shares. But, that could leave the company in a difficult position where a major shareholder may not want to vote in the interests of the company, or might be trekking in Patagonia and be unreachable, leaving the company unable to make key decisions. So, you can choose that founders who leave will lose voting rights on their remaining shares. They’ll still be able to get dividends, etc., they just won’t have voting rights.

Founder Share Transfers

What percent of their shares can a founder transfer without needing investor consent?

Founders often aren’t paid a salary, so to help them get value from the company and to realise their startup dream without waiting years for a sale or IPO of the business, it’s desirable for a founder to have the right to sell some of their shares, for example as part of the next funding round. That will dilute the founder, for sure, but it’s a great way to turn those years of effort into cash, hopefully at the super-low 10% Entrepreneurs’ Relief tax rate. You may need to do some up-front persuasion with your investors to let you have this provision. A typical value here would be 10%.

What approvals will be needed for a founder to sell those shares?

Our goal is to allow founders to sell a modest percent of their shares at any time (assuming they can find a buyer, of course) without needing any consents or approvals. But, if your investors push back on this (this is really something that is at their discretion) then try going back to them offering that board approval will be required. Or, if there’s an Investor Director on the board, you could go further and agree that Investor Director consent will be required too. If your investors won’t agree to any of this, then you’re back to the normal position of needing investor consent to transfer any of your shares.

Founder Salary

Will the founders be paid a salary?

Often in early stage startups founders don’t pay themselves a salary, and investors expect that they won’t do so for some time. But founders have mortgages to pay too, and they may have invested a lot of their own money into the business already, so they may need and be expecting to be paid a salary – see our founder salary statistics.

How much is the founders' annual salary?

What approval is needed to increase a founder's salary?

To avoid the founders deciding to pay themselves any amount they like, investors typically require at least board approval for a founder salary raise. In early stage startups the board consists of just the founders, so investors often also ask for the approval of an Investor Director if there is one, or otherwise Investor Consent. Our suggestion is to go with board approval with a review when the company reaches cash flow breakeven, unless your investors require otherwise.

Founder Loans

Is there any founder loan outstanding prior to completion?

Our data shows that founders put a median of £26,000 of their own money into the business before the first funding round. Why? Because nobody invests on just a PowerPoint slide deck, investors expect you to have built a prototype, validated the idea, etc.

If the founders have put money into the business, rather than just write it off as spent, it’s much better if that amount can be classed as a loan that can be repaid later, or turned into equity in a later funding round to reduce the founder’s dilution in the round.

How would you like to treat the loan?

It’s rare that investors will invest in your business only for you to take their money back out of the business to repay yourself. But, if you’re able to persuade your investors to recognise your loan as a debt repayable at, say, the future sale of the business, or as a loan conversion that can be turned into equity at some future time, then that’s a great way to get future value from your loan.

If the founder loan will convert into shares in this funding round then make sure to add the founder to the round as a converting investor. More on founder loan conversion here.

Warranties

Warranties liability cap

In the case of a breach of the warranties, it’s customary to cap the liability of the founders to either their annual salary or capped at a specific £ amount. For example, if you’re raising £500K and there are 2 founders then a cap of £25K per founder might be appropriate.

Warranties liability cap amount, per founder

Selecting a specified amount is useful where founders aren’t initially being paid a salary, as obviously 1X a salary of zero isn’t much of a liability incentive.

You can also specify that the founders have no personal warranties liability at all, so the investors can only claim against the company. Which is obviously desirable as a founder, the challenge is the investors may push back on that and demand that the founders have some level of personal liability, so they can claim against the founders if e.g. the company is insolvent at the time of the claim.

For how many months do warranties apply?

The warranty period is capped to avoid creating an open-ended obligation on the company. This is really important, without this cap your investors could make a claim against the company years later, for something you thought you’d closed the books on ages ago. We recommend 12 months as the warranty period, but if there are circumstances where you need longer, e.g. your investors would like it to span your next confirmation statement or company tax return, you may need to agree to that.

Completion Conditions

Directors and Officers Insurance

Directors and Officers (D&O) Insurance covers the directors of the company if they get personally sued by an investor, customer, etc. It’s good practice to have this in place once your business has investors, users or customers. In some cases your investors might want you to commit to actually having that in place within 3 months of closing the round, if you want to offer this commitment you can do that here. Of course you can always get such insurance regardless anytime, this is simply about committing in the Term Sheet and Shareholders Agreement to do so.

Keyperson Insurance

Keyperson insurance pays the company if one of the insured founders or key executives dies, etc. It’s a bit of a luxury thing for an early stage startup to spend money on, but if your investors are asking you for that (they must want to protect their investment in you!) you can specify that here and we’ll add wording to the Term Sheet and Shareholders Agreement saying you’ll do so within 3 months of the round closing.

Fees & Exclusivity

Will you agree to pay the investors' legal fees?

In the old days the company and each investor would engage their own lawyers. If you had a Lead Investor, they would ask the company to pay their legal costs. Our goal is that nobody needs lawyers, for a dramatic time and cost saving all round.

If your lead investor (or other investors, if there’s no lead investor) want to use lawyers, sure, but the idea is that they pay for their lawyers themselves. Hopefully that’s something you can agree on. But occasionally a lead investor (or other investors, if there’s no lead investor) may insist that you pay their legal costs. If you’re okay with that, you can specify that here.

What is the maximum amount of the investors' legal fees you'll agree to pay?

How many days exclusivity are you offering to your investors?

If there’s a lead investor they often ask for an exclusivity period during which you agree to not discuss or negotiate a deal with anyone else.

Our suggestion is to not offer an exclusivity period unless a lead investor specifically requires it.

Social Impact

A small but growing number of companies include social impact, not-for-profit or similar provisions in their Articles, containing wording that requires profits to be kept within the company, requires the company to have social impact goals, etc. While these ambitions are noble, they often include provisions like an Asset Lock that can make the company less attractive to investors who aren’t looking to invest in social impact companies, as these provisions can limit their return on investment. So, only select this if it’s something you and your investors both want.