Read transcript

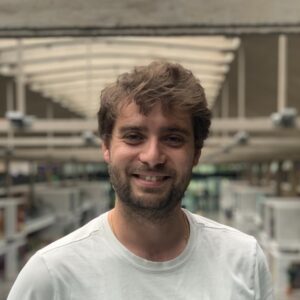

Today I’m delighted to talk to Hamza lecture at Cambridge Judge Business School on taking on Goliath.

So in some cases, you have a new startup in a space that’s never been done before, at least you think it hasn’t been done before, but pretty much nothing is new.

In other cases, you’re a disruptor.

You want to take on the insurance industry.

In the Seed Legals case, we’d like to take on, in a sense, the legal industry.

How are you going to take on a big player?

Are you gonna partner?

You could go to head, what’s the strategy?

And so we are going to learn from the finest in terms of the strategy, the things that you may have thought about, the things you never thought about, and coming from a university lecturer, probably the big picture things that are slightly different to the usual startup thinking.

So without further ado, let me hand over to Hamza to take it away.

And if you’ve got any questions, please pop them in the chat and we will try to get to get to them periodically during our session, and at least at the end of it, take it away.

Hums up.

Absolutely.

And Anthony, I just want to add to this, that, um, please, please, you can jump in because you’re the moderator.

Um, if, if I’m getting too entangled in my own thoughts and you feel like, uh, something needs to be, um, sort of explained a little bit better.

So, um, so just to make sure that, uh, you know, it’s a level playing field, let’s put it this way for, uh, for everyone.

And it’s an interesting and useful, uh, session as well.

So, um, just to, uh, just to set the tone, um, we will be talking a bit about the predictable lifecycle of companies, and then we will take on the original, uh, definition of disruption and why it’s not that useful anymore, and what the new, uh, what the new definition of disruption is that is actually working these days.

And, uh, last but not the least, the shift away from products to platforms and platforms to ecosystems and what kind of, um, strategies, uh, and policies you need to think about, uh, when you are moving away from products to platforms and then becoming a part or an, uh, of an ecosystem, or becoming an orchestrator in an ecosystem.

So let’s start off with the very cheerful topic of death.

So all companies die either through mergers and acquisitions or through bankruptcy.

There’s no question about it.

So there is this, uh, professor, um, called, uh, Jeffrey West, who was originally a theoretical physicist and eventually entered into the, into the sphere of commerce.

And, uh, he brought in a lot of maths with him.

And as part of his, uh, analysis, uh, of his seminal, uh, work called Scale, it’s a book that he released in 2016.

He plotted, um, the, the demise of US publicly traded companies.

And you can see that the vertical axis over here is the probability of survival.

And the x axis is the company’s age.

The lines that you see over here are revenues.

Okay?

So one of the things you will notice over here is that, um, we all imagine that, uh, the bigger the company, the more resilient it is to failure.

Actually, it doesn’t matter if you do two take out anything, which is, you know, too early, never gets funding.

I mean, that’s a completely different story, but, uh, anything which has some revenue, um, has roughly the same level of probability of dying, either through bankruptcy or liquidation or through somebody else buying them out.

Um, very, very close lines.

What is quite interesting is that the probability of death increases, um, with time.

So if you are kind of new, the first four years, the chances of your survival is, uh, 80%.

The moment you are 10 years old, your chances of survival is, uh, 30%.

And by the time you hit 40 years old as a company, uh, you basically are going to die in all likelihood, right?

And the reason for that, out of a lot of analysis is this, that companies just like, uh, uh, human beings, uh, atrophy.

And, um, in the case of human beings, atrophying is, you know, new cells, uh, stop forming at the rate at which they’re getting destroyed.

So we get old.

Um, in the case of companies, it is innovation.

So companies become more and more and more rigid.

So new ideas and new concepts and new business models bubble up less and they get really stuck in their old ways of doing things.

And that is the reason why they die.

So very similar to how human beings operate, and it’s getting faster, which is, uh, which is great news for startups, by the way.

So on s and p 519, uh, 58, if you were in the standard and poor, um, index, which is a D index for the US Stock Exchange, um, you could expect yourself to be there for 61 years, but in 2016, you can just expect yourself to be there for 18 years.

So there is a 71% drop in lifetime.

So say 60 years ago, you would’ve lasted for longer.

But now disruption is so fast that it is decreasing in size, geometrically, same as with Fortune 500, um, the Fortune five minute companies that you had back in 1955, only 61 of them are surviving today.

So it’s a 12% survival rate.

So the probability, so just to sort of recap, the probability of, uh, surviving either m and a or bankruptcy, uh, has, uh, no implication on the size of the company.

And when it comes to really, really large companies, um, their, their speed to death has increased several magnitudes. Okay? So for startups, that’s fantastic news because, well, I’ll hop in, I’ll hop in here. Yeah, sorry, I’ll, I’ll I’ll hop in here quickly ’cause it’s, uh, quite interesting.

So two things. Number one is yes, as you said, you know, we’ve all, uh, familiar with, uh, you know, charts saying the chance of a startup making it past the first or second round is, is small. But in fact, that might, in a sense, be part of the better part of the whole curve. It’s the latest stage. It also means that you, you might want to sell or exit your company, not not leaving it forever. And the third thing is, I saw a tweeter, you know, with all the news at the moment about Google, and it’s kind of terrible, Gemini, a ai and the terrible things it’s coming up with someone tweeted, what’s the chance of Google not being around in three years?

And someone had said, you know, it’s non-zero, which is scary. And I was about to reply going, yeah, in the same way that an asteroid striking you is non-zero. But actually, you know, think about it. You never know. So, um, anyway, with thoughts of, of death, let’s move on to the next segment. Yes. So what, so let’s start off, because we’ve spoken quite a bit about disruption, right?

So it’s, uh, it’s important that we first establish what the original definition of disruption was. It was, it came from this, uh, professor called Clayton Christensen, uh, from Harvard. Uh, incredible person, uh, came up with this, um, this theory that he worked with the CEO of Intel with. And, uh, this is a picture from Game of Thrones, um, and which, uh, uh, John Snow is the only one who is, uh, going on against this entire army, uh, that wants him dead, right?

So this is roughly what disruption is like from a startups perspective. You are lonely and you have all of these incumbents who want you dead. And so the, it starts off with this David and Goliath sort of perspective, small firms with fewer resources, it starts off with that belief that they can unseat incumbents. So if you have a startup idea, I mean, you do need to have the delusional belief that you can take an incumbent down.

If you don’t have that, the theory won’t work for you. The second thing is that they usually, disruptors usually focus on an, uh, uh, on an overlooked segment. And in most cases, it tends to be the vanilla or the low profit customer base. Uh, the ones that large companies tend to ignore. And they’re too focused on adding value by creating products that are more and more and more expensive. And, uh, the disruptor goes after the, the customers that basically, these guys barely want, they are there, but they don’t produce the most profits.

Then the disruptor’s new business model, mostly powered by new technology or some existing technology, uh, is able to make profits on that low end, and as a result is able to have some sort of a standard product that helps them go into the mainstream. And I’ll give some examples of that in the next slide.

Um, but the idea is that you go at the bottom of the pyramid and then you go up in the top. And when that happens, the market basically collapses. It’s like, uh, a star collapsing and becoming a black hole. So the, these incumbents collapse on themselves because their existing business model, their entire projections, all of those wonderful things just do not work in the face of this disruptor who has changed the underlying economics of the industry. And one of the things that I would like to highlight over here is that digital disruptors tend to take a lot of the profits away from the incumbents and give them back to the, to the customers in the form of lower prices.

So if, for example, the profit pool of an industry is a hundred billion dollars, the disruptor will keep 20 billion and become really big and will give back 80 billion to the customer in the form of lower prices. Some examples, you guys have heard of it a a million times, so, you know, have Netflix versus Blu-Ray, Amazon versus Bonds and Noble.

So it was a changing business model, how they operated as well as a completely different delivery mechanism. Amazon did not have, you know, bookstores, they did it through post and Netflix used streaming versus physical diss. So all very, you know, I’m sure you guys have heard of it. So why does it happen? Why do incumbents not see it coming? There are a bunch of reasons for that. The first one is their entirely new category of customers does pop up.

So for example, cryptocurrency, a lot of the earlier customers were not exactly, uh, the ones who were, uh, you know, linked to their bank accounts. Let’s put it this way, uh, not from my industry is a big problem. So Kodak, um, you know, right before it died, spent several, uh, several of its, uh, industry, uh, conferences saying that digital cameras and social media is not from the industry, and as a result died. Um, then there are new technological, uh, innovations that produce a whole new set of business models.

So you have on-premises servers versus cloud computing, uh, you have entirely new emergent ecosystem. So YouTube, for example, has massively displaced, uh, and disrupted traditional tv. Uh, so as Netflix, then you have the issue that a lot of incumbents start benchmarking themselves, um, on product features, which tends to be a really bad idea. They don’t look at the business holistically, they don’t look at what the customers want.

So they start saying, Hey, the iPhone is not as good as a Windows laptop. Guess what? It is not competing with a Windows laptop. It’s creating it’s whole new category. And this is, this is my two favorite ones. First one is that they have every CEO of an incumbent, you know, large organization has given a five year plan. So it is really hard to sort of roll back from that because if you go back to, um, your board and say, Hey, the projections I gave to you, now they’re getting disrupted.

It tends to get you fired. And the second one is that disruptors in the start tend to be unprofitable. So the incumbents tend to say, Hey, yeah, I have a man, uh, I am a margin of 40%. And that, uh, you know, guy or girl over there has a profit margin of 10%. What they do not know is that when this thing scales and takes over their profits, um, they would have a profit margin of minus 10%. Anthony, you wanted to say something? Yes. So, um, this is actually quite fascinating because some might be aware, but, uh, you know, seed Legals is kind of my third foray into the space of disruption.

And it started in a much bigger way for me back in my days with kaza. So back in, you know, for those who know Kaza, who might be a bit older, music file sharing, and at the time, uh, the CD business selling CDs was the way to sell music. And it was a $10 billion a year industry that was declining at a billion dollars year a year, year on year, uh, thanks to the rise of P two P online, you know, downloads and so on.

And, uh, you know, I personally, along with our CEO went to see the major music labels in New York and presented a PowerPoint on how we could build a licensed music store. This was in the days before iTunes and, uh, showing how, you know, streaming, uh, you know, revenue would surpass. And instead of licensing the content, they sued us. They wanted about a billion dollars. So I learned the first, uh, thing I learned in the space was that, uh, the incumbents, the existing players would often try to pretend that the world isn’t going to change and sue out of existence, those who want to change it.

But technology is inexorable. It’s, you know, it’s, uh, fighting the tide is just not gonna work. It took like 20 years until finally, you know, online streaming revenues surpassed CDs, but it sort of decimated the music industry and it’s only being rebuilt. Now, my second foray was in BBC iPlayer days and post BBC, where the broadcasters, the smarter ones, saw that you didn’t only need to watch it on telly tonight, you could watch it on any device tomorrow, um, which was great, but they never took the next step of, uh, redefining what is content.

And they despised the YouTube’s cats on skateboards, low quality at buffers. And I was thinking, and they went, it’s only kids watching this stuff. So they denigrated the competition with the, the technological less good features on the internet.

But guess what? The internet’s now the only way I get 4K, I don’t get it on broadcast. So, and they also look, said, it’s only kids, but kids grow up. And so I was deeply disappointed and could see that broadcasters would become, you know, a, a minority player in their own space because they just defined the competition as other broadcasters, not the way the world was really going. So, um, I’m quite intrigued, uh, now in my current space with, uh, you know, legals.

And also you want to make sure you’re not out disrupted yourself. Maybe I think I’m a disruptor and one day everyone will go and do it. I just use chat GPT, uh, for my contracts. You know, I don’t need a platform. So you always have to, um, if if you are not looking at your own disruption every day, you’re sentenced to be, you know, dead in the long term. Anyway, back to you. Absolutely. So we, we spoke a bit about the theory of disruption.

We spoke about Clayton Christiansen’s, uh, definition of it. And this is, you know, this is the sort of the classic visualization of it. You have the high end of the, of the market incumbents keep on adding things like imagine, you know, business class, first class, there might be some other class that goes above that. You keep on adding that up because it produces the most profits. Um, your disruptor tends to come at the lower end of the market, which is least profitable. And over time, that sort of vanilla offering become, goes into mainstream and it collapses.

And so, you know, you know, you, you know this about Kodak, great, great film reels, you know, they keep on producing more and more, um, you know, cameras that were they fantastic Blackberry, uh, whether it’s physical keyboard kept on going after the high end of the market, and then you have Ryan Air Robinhood, uh, very, very simple products, low cost going for the detailed customer and then became mainstream.

All of your airlines, basically, the mainstream airlines no longer really make money. So, you know, it fits that very well. But today it does not really explain a bunch of stuff. So if you look at Tesla or the iPhone, it actually goes down like this. Um, it goes, it went from the high end of the market and then disrupted the mainstream and completely changed the industry, uh, while retaining quite a bit of the, of, uh, sort of the characteristics of a disruptor.

And, and that means that the theory is now going to struggle quite a bit on, on trying to explain how this is happening. Even Uber started off with a shop for service and then went mainstream. So it, it breaks the theory. So we need to figure out what the new one is, right? So the classic disruptive innovation is now table stakes. So I’m not saying that you don’t use, uh, Clayton Christenson’s, uh, definition of it.

So, you know, David versus glide focus on an overlook segment, upgrade to mass market, but these are table stakes. What else can you do to be successful? And for that, there are three more dimensions that we do need to look at it. Number one is dramatic simplicity. So it’s not just simplicity of the product or, you know, just the proposition, but the value chain, the operations, and so on so forth. Then because of the high level of digitization, we now have, you know, the internet.

Now with ai, uh, startups need to take on an algorithmic approach, which is, again, significantly different from the original sort of design that, uh, came in the theory for disruption. Last, but not the least, it’s customer centricity and connectivity, and how do you form a community around it. I will quickly cover these points, and then we will move on to, uh, products and platforms. But near disruption in so many words is the table stakes that we have now, along with these three dimensions. So, dramatic simplicity, as I’ve shared with you before, starts off with propositions.

A good example here is Google. And so Google introduced pay for performance proposition, which was fundamentally different from the eyeballs and impressions of Leg Legacy media. You know, if you don’t know what I’m talking about, TV is usually measured by eyeballs, number of people who have, who might have seen it based on a sample, um, or impressions. But in the case of Google, as most of you know, you can pay for performance.

If somebody buys something off the website, that is the time when you buy, when you pay for it. And that entire loop of getting a visibility over the internet is fundamentally different from what the, from, from what broadcast does and broadcast is, and has been disrupted for the past five, six years. Most of these companies, the very large ones, are merging or collapsing or going through bankruptcy as a result of this one fundamental change that came in completely changed the business model value chain, uh, and process simplicity is equally important.

So again, I gave an giving an example of Sky, you know, an ad is short planning team decides where to plug it in. Purchasing team goes and buys the spots. Ads are compiling compatible formats and sent to different forms of, uh, you know, media outlets, ads are aired. And then there is some sample study that happens and comes back. And this whole thing can easily take six to eight weeks and up to even 50%, uh, 50 plus people’s time.

So very expensive value chain, right? All the steps that are being taken in the case of YouTube, you know, and add a shot, you upload the thing, make some bids, and off it goes. And then a day later you get, you get to know the impact of it, and that is very, very disruptive and by several magnitudes. So we are talking about going from 50 people’s worth of cost to under three people. And so this is a geometric decrease in cost for, um, for advertisers, for example.

And as a result of so many other wonderful things that YouTube does, it tipped the balance away from away from broadcast an algorithmic approach, and I’m spending a little bit more time over here just so that, you know, we understand how to practically implement these things. Algorithmic approach is, well, is a set of heuristics, uh, software and AI to lower cost of goods sold again by several magnitudes. So a good example here is that of e-commerce versus traditional retail.

In traditional retail, a procurement and pricing manager sets some meetings, sits together, picks up an Excel sheet, and approvals are set on budgets and ta ta. There is a lot of time that takes, and it then goes to the physical location, and it takes several days at the earliest and several weeks at the latest to make this happen. In the case of e-commerce, it is, you have scrapper bots that go and they scrape prices of other websites. If a price shift is caught, is caught, uh, computations kick in and they lower prices automatically on the e-commerce websites, similar products, uh, prices are updated almost immediately, and if sales climbs, the new stock is ordered automatically, and this can take between few seconds to a few hours.

So again, the magnitude of difference is huge, and that, again, can collapse and incumbent. And that explains why Amazon, which is where this happens, is a, you know, is a fantastic example of, of, of a disruptor. So speaking of Amazon, is customer centricity just a mission statement?

So Amazon has this lovely, uh, you know, mission statement that they have on their website, which is to be the earth’s most customer centric company where customers can find and discover anything they want. And they are customer, you know, generally a customer obsessed company. So they use the word customer a lot of times, but is that just plus? Is that just, you know, something that people say to feel good about themselves? And the answer to that is no, actually, customer centricity is also a part of strategy.

Um, customer centricity in technical terms is a self-organizing community. And so how do you form a self-organizing community? Do you put up forums? Yeah, I mean, sure, you could have some practical way of having it on your app, having it on your platform, so on, so forth. But the idea is that, A, they should be self-organizing, and b, you are not pleasing everyone. You’re pleasing the ones who matter, and the ones who matter are the ones who bring in other people over.

They are advocates of your, of your brand, and that is how you keep the community happy and nourished and thriving. So let’s talk a bit about, uh, moving away. So we’ve talked about the life and death of companies and that large companies die and have been dying very quickly lately. Then we’ve talked about disruption. We’ve talked about how, uh, the new disruptors do things differently, um, over and above the traditional definition of it, which was an algorithmic approach, dramatic simplicity, and building a thriving community.

Then we are going to talk a little bit about moving from products to platforms and to ecosystems. So the original form of, uh, business since the, uh, since we’ve been able to record history, has been about selling products, right? So a product could be a bar of chocolate, like Mars over here. You could have a Volkswagen Beetle, or you could have a film.

A film is a product as well. Um, and so in order to define what a product is, it’s important to, to be able to clearly put some checks on it. So product is a good, or a service that is consumed by a user in almost all of its entirety, usually by paying some price for it upfront. So it’s usually a single revenue stream. Sometimes it could be more, it could be a car plus, you know, it could be some services you get with it.

But the big thing about, um, products are that they do not connect consumers to the suppliers, uh, that constitute the product. So for example, when you go and buy a car from Volkswagen, you do not interact with the, with the company that has put the tires on, on the car, for example. Um, and as a result, there is also no direct feedback loop. You could have some market research like surveys and so on so forth, but there is no direct feedback loop, which happens very quickly that otherwise happens on platforms.

So this is what, uh, you know, at a very broad level is, is what a product is. It’s a very simple transaction. So what are platforms? So platforms are basically, um, platforms are basically not products, but they are, um, a place where users and suppliers are able to connect together and they’re able to generate feedback loops.

These are the feedback loops, right? The yellow and the blues. The more these feedback loops exists, the stronger the platform is. That means if you have more users, you will have more suppliers. If you have more suppliers, you will have more users. And this is known as network effects and very much simplifying this. There’s a lot of math that goes behind it, but in a nutshell, this is what it’s, um, and both of these sites feed to each other.

It’s almost like an infinite loop. Of course, you need to get to a critical mass of both users and suppliers, uh, until the network effects kick in. And, you know, there are different strategies for that, and we can discuss that in the q and a, uh, but this is how platforms work. But the question is, is, is platforms just a thing of the internet? And the answer to that is not actually, uh, platforms have been around, but in non-digital forms.

So you have auction houses, platforms, you know the link, uh, artists to buyers. You have Sunday markets, you know, you go to London, there are Sunday markets, you go and buy, buy food from there, or whatever else you feel like buying. And even universities, this is, uh, King’s College at Cambridge and universities are great platforms as well, because, uh, they bring academics to students, right? So not a new concept, only it has been digitized and it is now running at very, very low cost and at speeds that we could not really think of back in the day.

So multi-site platforms, this is the framework for the strategy that you need to think about when you’re thinking about multi-site platforms. So if you have a startup that wants to be a platform that connects users with suppliers, uh, and also generate network effects, these are the four things you need to think about.

And I can, obviously, there are any specific questions, I will answer them as part of the q and a if we have the time. But it is first is number of sites. There should at least be two of them. Uh, there are a lot of other platforms that have more than two. So for example, LinkedIn has recruiters, advertisers, and people looking for jobs. But it is actually difficult to have a balancing act when you have more than two. So if you are a startup, I would say start off with two and until, unless that gets stabilized, do not be more adventurous and add six more sides because that’s the fastest way to die.

Then designing quality does matter. Although features and quality, uh, are not, uh, do not completely stop a user from switching, they definitely produce, uh, a lot of friction in the process. So make sure that if you are going against some competitor of yours on some dimension, you are better off in terms of design quality. Then there is pricing.

Pricing is not straightforward for platforms. You usually discount one side, uh, or make it free, and you charge another side for the privilege of it, right? So for example, um, in the case of Amazon or eBay, they charge transaction fees to the sellers. They do not charge transaction fees to the users because the profits are being captured by the suppliers, so they know that they can afford it. But if you start charging the users for it, you know, you end up being in a, in a place where, uh, when not many of them will come in because prices would’ve risen for them.

So, so that’s one side, but then there are always other sides as well where they charge a user. So for example, there are some dating apps where they charge only men for the privilege of joining that dating app, and so they are charging us certain type of user. Then you have governance, which is the last one, which is in a nutshell means who do you allow into the platform and who do you kick outta the platform?

In a nutshell, that is what it means. So governance in this, for example, let’s take the example of X, you know, or Twitter, and, uh, governance is an issue there right now. How do you, uh, how do you ensure that you have good actors, uh, on that only and not do not have bad actors? And the governance problem has resulted in a wider spread strategy problem for Twitter, although I’m a big fan of Elon Musk, I do think he could have done a better job on this front.

So when you have a platform that becomes big and powerful, it starts becoming multi-sided. But after being multi-sided, that is, it has more than two sides. It starts connecting with more platforms and becomes what is effectively known as an orchestrator. And an orchestrator, uh, starts connecting itself to multiple platforms.

So you would say, you know, PayPal is an orchestrator, um, in sort of the FinTech domain, um, you could say that, uh, Apple’s iOS is an orchestrator, uh, within the mobile domain that you have Uber as a platform that connects him to iOS. You have Facebook a platform which connects him to iOS. So iOS in itself becomes this orchestrator with its policies and its APIs that can control other platforms.

So the question then comes in, if you are lucky enough to have a startup that is now growing, uh, to become an ecosystem orchestrator, what should your strategy be? We will first look at some examples. I quickly talked about it. Um, the examples of industry lines. Uh, let me just go into this first and then we will go back. So this, the choosing the right strategy for an ecosystem is a game of dependencies.

So you want to always be in a position where other people are dependent on you, other companies are dependent on you. And the way to do that is, uh, a three step cycle. First one is to grow note firms. So even if there are people who are competing with you or companies that are competing with you, as long as they’re dependent on you, that’s a good thing. So you can think about Google’s Android and Samsung. So Google makes its own phones, but Samsung uses Android to also make its own phones. And then Samsung also has a lot of apps that help, uh, it to move customers from iOS to Android being hosted on, uh, the iOS store and vice versa.

So increasing note forms actually increases your power. So you need to look at your competition in a very different way, then you need to be the one who establishes the standards if you are in the place to do it. If you’re so small, nobody cares, then don’t do it. But for example, Chad, GPT, uh, open AI is basically establishing standards right now on ai.

And it was relatively small company to begin with. Nvidia, um, which is now multi-trillion dollars, uh, established the baseline for, um, for computer graphics, controls, the standards like anything. But what is the, probably the most important is that you can own the customer relationship. You need to be the closest to the customer. If you have multiple middlemen on middle platforms in between, you will have the least amount of power in the least amount of profits.

So when you look at these, uh, these strategies for ecosystems, you do ask that what, what is the plus side of an ecosystem, right? So the plus side of an ecosystem is that it causes industry lines to blur. So if I were to go back, sorry, if I were to go back to industry lines blurring, one of the questions I ask my students is, which industry does Apple belong to? Does it belong to computers?

Does it belong to media? Does it belong to variables, phones, software, consumer finance? I mean, which one is it? And because it’s an ecosystem orchestrator with multiple nodes at the end, it can be all of these things. Grab is a taxi service in, uh, Southeast Asia, and they do ride hailing. They are, they were, they are like a supercharged version of Uber. They do ride hailing grocery deliveries, they do mobile wallets, they give you loans, they allow you to make investments, and they allow you to get remittances something, which is very important in that market.

In the case of Amazon, we know it does just about everything. So it’s very, very hard to define an industry once it becomes part of an ecosystem. You can no longer say, this is no, not my industry anymore, which is something that Anthony referred to in his, um, in his journey, uh, as a, as a disruptor in a startup journey. So with that, it is now finished.

I’m going to shut down this presentation and I will let Anthony choose the questions that, uh, that you would like to, to discuss on this, uh, on this, uh, session. All right, well, thank you. That was amazing. Um, and uh, was really fascinating because as you were talking, there were a bunch of things that I had thought that at Seed Legals we did, but I never thought about it in that way. And so what I love about this is the strategic thinking that crystallizes things that you might have sort of felt like doing in the past.

And so the two, uh, key blocks that for me jumped out were, number one, how do you disrupt someone? And the three things were radical, simplicity, uh, algorithmic, uh, and customer centric. And, uh, you know, I had never, I mean, I’d not thought of it in those ways, but those are actually exactly what I look to do on a daily basis. And for me, the radical simplicity in the case of Legals is a law firm.

The output is a legal document. But for those watching this, I don’t think anyone’s ever looking for a legal document. You’re looking for investment or you want to hire somebody. So why go through the whole process of talking to a lawyer, talking to another, when you can just go and say, I want to hire someone. Here’s some data to show what the salary is. Click and, and you’re done. The, the algorithmic is something I need to watch out, that I’m not gonna be out as disrupted by something with their highness. And the customer centric has been a, a passion point for me.

So I think once you understand it, uh, strategically it will help shape your thinking. The second area that you covered, which was, uh, the other three things. Number one is always be a position where, uh, customers are or people are dependent on you. I like to think of it as where you power other people’s businesses rather than creating a Exactly, you know, drug dealer dependency. Exactly, exactly. Established standards. And I’ve never really thought of it, you know, in that way, but, you know, the goal at Seed Legals initially, ’cause we were the minor player, was to reflect what was market standard.

But as you’ve got more people using you, you can now aim to become the market standard and, and the leader. And the other one is to own the customer relationship. And there I think that’s really important. ’cause I see lots of startups on seed legals, and sometimes they’re looking, should I go B2B or should I go B2C? And if I’m building some product, will thousands of customers go to me or they go to somebody else and they’ll use me?

And obviously you always want to be in the position where you own the customer relationship. ’cause that gives you the power. If you are a service supplier to someone else, you are no more valuable to them than the cost of them switching to another service supplier and then your business is gone. So those are the key things, and if anyone’s got questions on those, we’ll get to those in a minute. Then the other one that, um, I want to ask you about is, is there a disruption opportunity?

Or maybe you see it as two minus, just a feature tick away that, uh, providing a a, a recurring billing model when the incumbents have got a one off model. So, you know, maybe others are selling you a high price item, you’re doing it as a, a monthly recurring. I mean, that’s what’s powered the software, SaaS business. Any thoughts on that? So I think there are, um, the reason for taking on a subscription is if you are able to extract some value every month, I mean, that, that’s the, the nub of it.

Why would I want to take on a subscription unless, until I’m getting, uh, some value, which is more than the value I got last month. So in the case of telecom companies, for example, it tends to be that if there are more people coming onto the network that, you know, I can make cheaper calls, whatever. Uh, in the case of Netflix, it is more content that comes in that justifies having their subscription. Now, for example, if you have, uh, if you have a, uh, have a product that is better suited for a single transaction, don’t put it on subscription, because if you’re not updating it, if you’re not adding more value that customers really, really want, then you’re shooting yourself in the foot.

Not everything, uh, and not everything solution is, uh, software as a service. However, if you have, um, a cloud-based offering, which allows you to dramatically lower your prices, then just shoot it out at a lower price. So if your competitor is sitting at a hundred dollars and you can sell this thing because of your algorithmic approach and your infrastructure allows you to scale it and sell it at $10, sell it at $10.

You don’t have to put it at dollar one per month because customers might not still want it because they consume it in one go. It’s quite interesting, the whole recurring billing thing, and it’s fascinating, uh, particularly at Sea Legals. ’cause one of the things is sometimes it it’s the case. Your customers are looking for one-off billing, uh, they just want something occasionally and want to pay for it, then they don’t wanna pay all the time.

On the other hand, investors usually value recurring billing. And you know, VCs tell me that they’ll value recurring billing, uh, in a company valuation, that investment time at three to four times what the equivalent of one-off billing will be. And there’s your challenge. Are you trying to satisfy your investors ’cause you want to investment or are you trying to satisfy customers? Otherwise you don’t have a business in the first place. Yes. So let me turn now to marketplace.

So, um, one of the, the, the two issues with marketplaces, and I’d love your thoughts. Number one is the getting started problem. So I was at a presentation years ago, uh, with uh, Reid Hoffman from LinkedIn, uh, talking, and he was saying, first build a utility and then build a network. ’cause no one would use LinkedIn if there was like nobody else you knew on the platform. So you had to get some value from it first. So that’s part one. And part two is how do you deal with the asymmetry?

So you want to make a, you know, an Uber and there are a million passengers, but only a thousand drivers. Which side, how do you set up your website to, uh, and, and your, uh, you know, uh, marketing so that you get, you don’t have one side dramatically outweighing the other over to you? Yeah, absolutely. So that the highly technical term of this problem is known as the penguin challenge. So basically in the, in the Arctic where, uh, penguins are commonly found, um, there is a huge line of them standing at the edge of the glacier where they’re really, really hungry and they want to jump into the water to, to find fish to eat.

Uh, but they’re also scared that there a seal might be there to eat them up. So they all are looking at each other to see which one will jump first. And that is, um, that is a problem with platforms that everybody is looking at each other and saying, okay, which one, who’s taking this plunge first?

And after that I will do it. And, uh, it’s also known as the critical mass problem. And answering your question about the, um, the, on the second side is to how do you, how do you fix that problem? The method to that is known as the Z method, and the second one is known as a thick market method. So z method, as it sounds, or a zed method for British, um, is that, um, depending on which side is more scarce, you first capture that side and then you make it, then you make the other side serve that one.

So for example, there is a trucking platform in the, in the US which is now very popular. And the problem that they had to solve was that they wanted to make a platform that allowed you to book a truck, right? But truck drivers were, were a lot back then. Now they’re a little short, but the demand of, uh, of having them was, was not sufficiently there.

And people were not on the client side, were not very comfortable using a platform to place these large orders, right? And then, um, so what they did was they captured demand and then they would run to, uh, a lorry station and then they would give that demand note to the truck driver who would then go and pick it up. They did that for several months, but by that time, the critical mask of of demand became, became there and the supply, which was a lot, was, was not never a problem at that time.

So the Z method is I go with demand or whatever is scarce, solve that first, give it to the, to the side of the platform, which is abundant, then go back to the demand side, then do it. So you keep on doing the Z method until you get to the critical mass. That is a very clear strategy of doing it. So that’s one. The second one is something known as a thick market. So a lot of people when they start off, a lot of startups when they start off with platforms is that they do try to do everything at the same time.

Or, you know, I’ve put up a FinTech platform, I will do loans, I will do mortgages, I will do this, I will do that. And what it, what they end up doing is they don’t do anything good on any of them. So what you need to do is you need to select a very focused view of things. So for example, in the case of this trucking company, they became very, very focused on, on the state of Texas.

They did not offer the platform across the us It was only that when it became a thick market in the US in the, in Texas, that the move to the next state, in the state after, until the whole country became a thick market, because it would’ve been useless to offer it to everyone when you would not have enough rux or enough customers to make it worthwhile in the platform would’ve died. Um, so yeah, I mean these are the two things, the z method and the thick market solution.

Okay, that is, uh, fascinating. Um, so I think you, and, and maybe every marketplace, uh, provider works it out pretty quickly, but it seems count, well, it might be obvious or maybe it’s counterintuitive to focus on the difficult part, the limited part first. ’cause you think the other one’s easy. I’m just gonna the website and get thousands of people signing up. But in fact, all your efforts should be focused on the other part. All right, now we are going to turn to a question, which is how would you approach an untapped market that is a combination of small sort of cottagey cottage industry players and a few big players?

Is there anything there that might suggest may, maybe you’ve got a fancy name for it, the W method, um, but, uh, uh, but, but would you perhaps go to take on the smaller players first or take on the bigger players or go somewhere in the middle? Uh, any thoughts on that? So I’m not really sure whether it’s an untapped market, if you have very large dominant incumbents and a cottage industry, right?

So you Have very good point, yeah, You have both the, the, the, the tick front and the long tail, right? I mean, so it’s not exactly untapped. Having said that, having said that, if the cottage industry is, uh, fairly standardized, that is, you know, ev it’s a cottage industry. Let’s say it makes milkshakes and everybody’s milkshake roughly tastes the same, then uh, you should go after the fragmented lot because they are the ones who will collapse the fastest.

They, they don’t have the money, you know, the resources, et cetera, et cetera. But it really depends on whether that cottage industry is deeply differentiated or not. In a lot of cases, cottage industries tend to be differentiated because people want that specific thing from that specific place. Okay. Alright. So the, the next question then, which is a fascinating one, is, comes down to you you’re disrupting someone else’s market.

What’s to prevent them doing the same as you and putting you back out of business and so on. And, uh, you know, maybe talk about the generic case and then I’ll talk about, you know, our use case with, with law firms, uh, where, for example, what’s to prevent law firms, you know, innovating and doing exactly the same. I’ve got some theories on that, but I’d love to hear your theories, um, and on, on both what’s likely to happen and what you can do to avoid that happening. Yeah, no, so that’s, that’s again, fantastic question, right?

So, so there are a couple of things. I showed a slide about, um, about the blind spot of incumbents. So there is, uh, you, you do get the room to grow because they don’t take you seriously. They don’t take your way of doing seriously. So that’s one. Um, and as a result, if you get enough time, it shoots up, uh, and you can disrupt them. The second one is that, uh, surprisingly disruptors can become compliments.

Compliments mean that they go like, you know what? Let them deal with this. If somebody of, uh, you know, uh, a customer which is looking for a more standard approach, uh, we will send them over to your company and let’s do a small revenue share. So it becomes a compliment. And the third one is that if some CEO gets changed and the management team wakes up, they usually end up buying the comp, the the disruptor because by the time the disruptor has be, has, you know, has really gained traction, it’s too late for them to build.

So that is the time where the venture capital firms, uh, get their exit. Okay, so my, you know, first learning from this, uh, about this was back in my kaza days where, you know, the music, uh, industry, uh, was selling $10 billion a year. Some others were making tiny amounts of money. And of course the incumbent says, yes, this one day might be a problem, but actually in the short term, I’m much better off keeping my high prices.

And it’s a real dilemma. ’cause if they keep their high prices, the smaller player is just gonna gain more and more market share for one day, it eats them. Uh, but if they reduce their market price, their, their, their pricing, they’re gonna take 5 billion or whatever off their, uh, revenue just ’cause some person is making a hundred million a year on the side. It doesn’t make sense. So what should be, how do you tap into that strategy you may find, um, and the great example for me was Skype and phone companies, right?

So your phone company was charging you, you know, 10 pounds a minute or some ridiculous amount for call to Australia. Skype’s doing it for free. They’re making no money from it, but they screwing the revenue of the phone company big time. At what point does it make sense to set yourself up as an acquisition for the large player? At what point is it to actually make sense to just be seriously disruptive?

You know, TransferWise putting on buying Tube ads saying your bank is trying to screw you, um, was seriously aggressive, um, and, and nobody bought them at that time. They could have bought it for a hundred, the cost they could buy them now. So, and then it’ll just eat the bank alive later. Absolutely. Like, I, I completely agree with you. It’s, um, managers of very large companies tend to have, uh, big egos and big blinders.

And it is basically hubris, which is the big enabler of disruption. If we, if we were to distill it down to that, which is the way hubris is, the way I would define hubris is, you know, the way I do things, the way I look at the world is, is the best, most correct way of doing it. And a disruptor takes advantage of that. Alright, so that was fantastic and I think I, I I love the, uh, the ending of that, which is the hubris part.

So if you’re a small startup and your investors are saying the big company’s gonna do exactly the same and put you out of business, you know, the answer realistically is a, is a set of a few things. Firstly, you know, often they won’t look to disrupt their own market. Secondly, they’re often completely blind to the way they’re doing things. Thirdly, they want often the existing world to stay as it is, and they just don’t want change. But your customers are wanting change. And I was at a, a law tech, uh, uh, event in, uh, the US at the end of last year.

And there were the CEO of two of the largest, uh, the champion people of the two of the largest law firms on stage. And someone was talking about the, uh, billable hour. They, they make hundreds of billions, you know, in, in, in legal fees. And, uh, they were basically, uh, defending the billable hour. But what they’re forgetting is that AI is going to reduce the cost per person to, or of advice to zero, and the billable hour just isn’t going to stay.

And this has nothing to do with Sea Legals. This is all about ai. So, you know, the law firm is now, some of them are in a panic about what to do. Some of them are just going, we are just gonna stay with our billable hour for as long as we can. And, uh, we’ll see what happens in the meantime. You know, thousands of startups are coming to play to eat away at all of that, the pieces of that pie. So it’s gonna be super fascinating to watch.

All right. And then the other thing, uh, you know, just as a personal example, a couple of startups ago when I was doing a social TV app, you know, I’d, I’d wake up with a fear that Facebook or Twitter was going to do exactly what we were going to do. And my investors were saying, you know, what, if they do it, turns out they just never did. And they made some half-hearted attempts that didn’t work and they gave up. And, and so, you know, the, the fear that a large player is going to change what they’re doing to compete with you, I think historically turns out to be hardly ever the case.

Your much bigger problem is actually just finding consumers, turning it into a proper business model. ’cause it’s easy to disrupt someone else’s business, but much harder to actually make it a viable business yourself. You know, it’s easy to give away the free phone calls on with, with internet telephony, but how do you monetize it? And once you monetize it, maybe you’ve got the same problem as the incumbents. So, uh, all right, that, uh, I think any, any last, uh, items from you?

Hum. And then also are you okay if people contact you and can you tell everyone your contact details? Yeah, absolutely. So on the, on the slides I had uh, put in my email it’s uh, Hamza strategize nc. Um, it’s my startup. And yeah, it would be, I’m more than happy to, uh, to be contacted. Um, just saying that, um, I think my last thought would be that disruption is not for the fainthearted, but it happens more often than you think it does.

And so keep that delusional belief that your startup will work and just go at it. Alright, well thank you so much and I’ll end by saying that I don’t think that waking up in the morning with a goal of disrupting someone else’s business is a useful goal. ’cause it sets you off on all the wrong things and instead your goal is to provide a great product that your customers will love. Um, and use technology to do something that hasn’t been possible before.

And that will change everything.

Today I’m delighted to talk to Hamza lecture at Cambridge Judge Business School on taking on Goliath.

So in some cases, you have a new startup in a space that’s never been done before, at least you think it hasn’t been done before, but pretty much nothing is new.

In other cases, you’re a disruptor.

You want to take on the insurance industry.

In the Seed Legals case, we’d like to take on, in a sense, the legal industry.

How are you going to take on a big player?

Are you gonna partner?

You could go to head, what’s the strategy?

And so we are going to learn from the finest in terms of the strategy, the things that you may have thought about, the things you never thought about, and coming from a university lecturer, probably the big picture things that are slightly different to the usual startup thinking.

So without further ado, let me hand over to Hamza to take it away.

And if you’ve got any questions, please pop them in the chat and we will try to get to get to them periodically during our session, and at least at the end of it, take it away.

Hums up.

Absolutely.

And Anthony, I just want to add to this, that, um, please, please, you can jump in because you’re the moderator.

Um, if, if I’m getting too entangled in my own thoughts and you feel like, uh, something needs to be, um, sort of explained a little bit better.

So, um, so just to make sure that, uh, you know, it’s a level playing field, let’s put it this way for, uh, for everyone.

And it’s an interesting and useful, uh, session as well.

So, um, just to, uh, just to set the tone, um, we will be talking a bit about the predictable lifecycle of companies, and then we will take on the original, uh, definition of disruption and why it’s not that useful anymore, and what the new, uh, what the new definition of disruption is that is actually working these days.

And, uh, last but not the least, the shift away from products to platforms and platforms to ecosystems and what kind of, um, strategies, uh, and policies you need to think about, uh, when you are moving away from products to platforms and then becoming a part or an, uh, of an ecosystem, or becoming an orchestrator in an ecosystem.

So let’s start off with the very cheerful topic of death.

So all companies die either through mergers and acquisitions or through bankruptcy.

There’s no question about it.

So there is this, uh, professor, um, called, uh, Jeffrey West, who was originally a theoretical physicist and eventually entered into the, into the sphere of commerce.

And, uh, he brought in a lot of maths with him.

And as part of his, uh, analysis, uh, of his seminal, uh, work called Scale, it’s a book that he released in 2016.

He plotted, um, the, the demise of US publicly traded companies.

And you can see that the vertical axis over here is the probability of survival.

And the x axis is the company’s age.

The lines that you see over here are revenues.

Okay?

So one of the things you will notice over here is that, um, we all imagine that, uh, the bigger the company, the more resilient it is to failure.

Actually, it doesn’t matter if you do two take out anything, which is, you know, too early, never gets funding.

I mean, that’s a completely different story, but, uh, anything which has some revenue, um, has roughly the same level of probability of dying, either through bankruptcy or liquidation or through somebody else buying them out.

Um, very, very close lines.

What is quite interesting is that the probability of death increases, um, with time.

So if you are kind of new, the first four years, the chances of your survival is, uh, 80%.

The moment you are 10 years old, your chances of survival is, uh, 30%.

And by the time you hit 40 years old as a company, uh, you basically are going to die in all likelihood, right?

And the reason for that, out of a lot of analysis is this, that companies just like, uh, uh, human beings, uh, atrophy.

And, um, in the case of human beings, atrophying is, you know, new cells, uh, stop forming at the rate at which they’re getting destroyed.

So we get old.

Um, in the case of companies, it is innovation.

So companies become more and more and more rigid.

So new ideas and new concepts and new business models bubble up less and they get really stuck in their old ways of doing things.

And that is the reason why they die.

So very similar to how human beings operate, and it’s getting faster, which is, uh, which is great news for startups, by the way.

So on s and p 519, uh, 58, if you were in the standard and poor, um, index, which is a D index for the US Stock Exchange, um, you could expect yourself to be there for 61 years, but in 2016, you can just expect yourself to be there for 18 years.

So there is a 71% drop in lifetime.

So say 60 years ago, you would’ve lasted for longer.

But now disruption is so fast that it is decreasing in size, geometrically, same as with Fortune 500, um, the Fortune five minute companies that you had back in 1955, only 61 of them are surviving today.

So it’s a 12% survival rate.

So the probability, so just to sort of recap, the probability of, uh, surviving either m and a or bankruptcy, uh, has, uh, no implication on the size of the company.

And when it comes to really, really large companies, um, their, their speed to death has increased several magnitudes. Okay? So for startups, that’s fantastic news because, well, I’ll hop in, I’ll hop in here. Yeah, sorry, I’ll, I’ll I’ll hop in here quickly ’cause it’s, uh, quite interesting.

So two things. Number one is yes, as you said, you know, we’ve all, uh, familiar with, uh, you know, charts saying the chance of a startup making it past the first or second round is, is small. But in fact, that might, in a sense, be part of the better part of the whole curve. It’s the latest stage. It also means that you, you might want to sell or exit your company, not not leaving it forever. And the third thing is, I saw a tweeter, you know, with all the news at the moment about Google, and it’s kind of terrible, Gemini, a ai and the terrible things it’s coming up with someone tweeted, what’s the chance of Google not being around in three years?

And someone had said, you know, it’s non-zero, which is scary. And I was about to reply going, yeah, in the same way that an asteroid striking you is non-zero. But actually, you know, think about it. You never know. So, um, anyway, with thoughts of, of death, let’s move on to the next segment. Yes. So what, so let’s start off, because we’ve spoken quite a bit about disruption, right?

So it’s, uh, it’s important that we first establish what the original definition of disruption was. It was, it came from this, uh, professor called Clayton Christensen, uh, from Harvard. Uh, incredible person, uh, came up with this, um, this theory that he worked with the CEO of Intel with. And, uh, this is a picture from Game of Thrones, um, and which, uh, uh, John Snow is the only one who is, uh, going on against this entire army, uh, that wants him dead, right?

So this is roughly what disruption is like from a startups perspective. You are lonely and you have all of these incumbents who want you dead. And so the, it starts off with this David and Goliath sort of perspective, small firms with fewer resources, it starts off with that belief that they can unseat incumbents. So if you have a startup idea, I mean, you do need to have the delusional belief that you can take an incumbent down.

If you don’t have that, the theory won’t work for you. The second thing is that they usually, disruptors usually focus on an, uh, uh, on an overlooked segment. And in most cases, it tends to be the vanilla or the low profit customer base. Uh, the ones that large companies tend to ignore. And they’re too focused on adding value by creating products that are more and more and more expensive. And, uh, the disruptor goes after the, the customers that basically, these guys barely want, they are there, but they don’t produce the most profits.

Then the disruptor’s new business model, mostly powered by new technology or some existing technology, uh, is able to make profits on that low end, and as a result is able to have some sort of a standard product that helps them go into the mainstream. And I’ll give some examples of that in the next slide.

Um, but the idea is that you go at the bottom of the pyramid and then you go up in the top. And when that happens, the market basically collapses. It’s like, uh, a star collapsing and becoming a black hole. So the, these incumbents collapse on themselves because their existing business model, their entire projections, all of those wonderful things just do not work in the face of this disruptor who has changed the underlying economics of the industry. And one of the things that I would like to highlight over here is that digital disruptors tend to take a lot of the profits away from the incumbents and give them back to the, to the customers in the form of lower prices.

So if, for example, the profit pool of an industry is a hundred billion dollars, the disruptor will keep 20 billion and become really big and will give back 80 billion to the customer in the form of lower prices. Some examples, you guys have heard of it a a million times, so, you know, have Netflix versus Blu-Ray, Amazon versus Bonds and Noble.

So it was a changing business model, how they operated as well as a completely different delivery mechanism. Amazon did not have, you know, bookstores, they did it through post and Netflix used streaming versus physical diss. So all very, you know, I’m sure you guys have heard of it. So why does it happen? Why do incumbents not see it coming? There are a bunch of reasons for that. The first one is their entirely new category of customers does pop up.

So for example, cryptocurrency, a lot of the earlier customers were not exactly, uh, the ones who were, uh, you know, linked to their bank accounts. Let’s put it this way, uh, not from my industry is a big problem. So Kodak, um, you know, right before it died, spent several, uh, several of its, uh, industry, uh, conferences saying that digital cameras and social media is not from the industry, and as a result died. Um, then there are new technological, uh, innovations that produce a whole new set of business models.

So you have on-premises servers versus cloud computing, uh, you have entirely new emergent ecosystem. So YouTube, for example, has massively displaced, uh, and disrupted traditional tv. Uh, so as Netflix, then you have the issue that a lot of incumbents start benchmarking themselves, um, on product features, which tends to be a really bad idea. They don’t look at the business holistically, they don’t look at what the customers want.

So they start saying, Hey, the iPhone is not as good as a Windows laptop. Guess what? It is not competing with a Windows laptop. It’s creating it’s whole new category. And this is, this is my two favorite ones. First one is that they have every CEO of an incumbent, you know, large organization has given a five year plan. So it is really hard to sort of roll back from that because if you go back to, um, your board and say, Hey, the projections I gave to you, now they’re getting disrupted.

It tends to get you fired. And the second one is that disruptors in the start tend to be unprofitable. So the incumbents tend to say, Hey, yeah, I have a man, uh, I am a margin of 40%. And that, uh, you know, guy or girl over there has a profit margin of 10%. What they do not know is that when this thing scales and takes over their profits, um, they would have a profit margin of minus 10%. Anthony, you wanted to say something? Yes. So, um, this is actually quite fascinating because some might be aware, but, uh, you know, seed Legals is kind of my third foray into the space of disruption.

And it started in a much bigger way for me back in my days with kaza. So back in, you know, for those who know Kaza, who might be a bit older, music file sharing, and at the time, uh, the CD business selling CDs was the way to sell music. And it was a $10 billion a year industry that was declining at a billion dollars year a year, year on year, uh, thanks to the rise of P two P online, you know, downloads and so on.

And, uh, you know, I personally, along with our CEO went to see the major music labels in New York and presented a PowerPoint on how we could build a licensed music store. This was in the days before iTunes and, uh, showing how, you know, streaming, uh, you know, revenue would surpass. And instead of licensing the content, they sued us. They wanted about a billion dollars. So I learned the first, uh, thing I learned in the space was that, uh, the incumbents, the existing players would often try to pretend that the world isn’t going to change and sue out of existence, those who want to change it.

But technology is inexorable. It’s, you know, it’s, uh, fighting the tide is just not gonna work. It took like 20 years until finally, you know, online streaming revenues surpassed CDs, but it sort of decimated the music industry and it’s only being rebuilt. Now, my second foray was in BBC iPlayer days and post BBC, where the broadcasters, the smarter ones, saw that you didn’t only need to watch it on telly tonight, you could watch it on any device tomorrow, um, which was great, but they never took the next step of, uh, redefining what is content.

And they despised the YouTube’s cats on skateboards, low quality at buffers. And I was thinking, and they went, it’s only kids watching this stuff. So they denigrated the competition with the, the technological less good features on the internet.

But guess what? The internet’s now the only way I get 4K, I don’t get it on broadcast. So, and they also look, said, it’s only kids, but kids grow up. And so I was deeply disappointed and could see that broadcasters would become, you know, a, a minority player in their own space because they just defined the competition as other broadcasters, not the way the world was really going. So, um, I’m quite intrigued, uh, now in my current space with, uh, you know, legals.

And also you want to make sure you’re not out disrupted yourself. Maybe I think I’m a disruptor and one day everyone will go and do it. I just use chat GPT, uh, for my contracts. You know, I don’t need a platform. So you always have to, um, if if you are not looking at your own disruption every day, you’re sentenced to be, you know, dead in the long term. Anyway, back to you. Absolutely. So we, we spoke a bit about the theory of disruption.

We spoke about Clayton Christiansen’s, uh, definition of it. And this is, you know, this is the sort of the classic visualization of it. You have the high end of the, of the market incumbents keep on adding things like imagine, you know, business class, first class, there might be some other class that goes above that. You keep on adding that up because it produces the most profits. Um, your disruptor tends to come at the lower end of the market, which is least profitable. And over time, that sort of vanilla offering become, goes into mainstream and it collapses.

And so, you know, you know, you, you know this about Kodak, great, great film reels, you know, they keep on producing more and more, um, you know, cameras that were they fantastic Blackberry, uh, whether it’s physical keyboard kept on going after the high end of the market, and then you have Ryan Air Robinhood, uh, very, very simple products, low cost going for the detailed customer and then became mainstream.

All of your airlines, basically, the mainstream airlines no longer really make money. So, you know, it fits that very well. But today it does not really explain a bunch of stuff. So if you look at Tesla or the iPhone, it actually goes down like this. Um, it goes, it went from the high end of the market and then disrupted the mainstream and completely changed the industry, uh, while retaining quite a bit of the, of, uh, sort of the characteristics of a disruptor.

And, and that means that the theory is now going to struggle quite a bit on, on trying to explain how this is happening. Even Uber started off with a shop for service and then went mainstream. So it, it breaks the theory. So we need to figure out what the new one is, right? So the classic disruptive innovation is now table stakes. So I’m not saying that you don’t use, uh, Clayton Christenson’s, uh, definition of it.

So, you know, David versus glide focus on an overlook segment, upgrade to mass market, but these are table stakes. What else can you do to be successful? And for that, there are three more dimensions that we do need to look at it. Number one is dramatic simplicity. So it’s not just simplicity of the product or, you know, just the proposition, but the value chain, the operations, and so on so forth. Then because of the high level of digitization, we now have, you know, the internet.

Now with ai, uh, startups need to take on an algorithmic approach, which is, again, significantly different from the original sort of design that, uh, came in the theory for disruption. Last, but not the least, it’s customer centricity and connectivity, and how do you form a community around it. I will quickly cover these points, and then we will move on to, uh, products and platforms. But near disruption in so many words is the table stakes that we have now, along with these three dimensions. So, dramatic simplicity, as I’ve shared with you before, starts off with propositions.

A good example here is Google. And so Google introduced pay for performance proposition, which was fundamentally different from the eyeballs and impressions of Leg Legacy media. You know, if you don’t know what I’m talking about, TV is usually measured by eyeballs, number of people who have, who might have seen it based on a sample, um, or impressions. But in the case of Google, as most of you know, you can pay for performance.

If somebody buys something off the website, that is the time when you buy, when you pay for it. And that entire loop of getting a visibility over the internet is fundamentally different from what the, from, from what broadcast does and broadcast is, and has been disrupted for the past five, six years. Most of these companies, the very large ones, are merging or collapsing or going through bankruptcy as a result of this one fundamental change that came in completely changed the business model value chain, uh, and process simplicity is equally important.

So again, I gave an giving an example of Sky, you know, an ad is short planning team decides where to plug it in. Purchasing team goes and buys the spots. Ads are compiling compatible formats and sent to different forms of, uh, you know, media outlets, ads are aired. And then there is some sample study that happens and comes back. And this whole thing can easily take six to eight weeks and up to even 50%, uh, 50 plus people’s time.

So very expensive value chain, right? All the steps that are being taken in the case of YouTube, you know, and add a shot, you upload the thing, make some bids, and off it goes. And then a day later you get, you get to know the impact of it, and that is very, very disruptive and by several magnitudes. So we are talking about going from 50 people’s worth of cost to under three people. And so this is a geometric decrease in cost for, um, for advertisers, for example.

And as a result of so many other wonderful things that YouTube does, it tipped the balance away from away from broadcast an algorithmic approach, and I’m spending a little bit more time over here just so that, you know, we understand how to practically implement these things. Algorithmic approach is, well, is a set of heuristics, uh, software and AI to lower cost of goods sold again by several magnitudes. So a good example here is that of e-commerce versus traditional retail.

In traditional retail, a procurement and pricing manager sets some meetings, sits together, picks up an Excel sheet, and approvals are set on budgets and ta ta. There is a lot of time that takes, and it then goes to the physical location, and it takes several days at the earliest and several weeks at the latest to make this happen. In the case of e-commerce, it is, you have scrapper bots that go and they scrape prices of other websites. If a price shift is caught, is caught, uh, computations kick in and they lower prices automatically on the e-commerce websites, similar products, uh, prices are updated almost immediately, and if sales climbs, the new stock is ordered automatically, and this can take between few seconds to a few hours.

So again, the magnitude of difference is huge, and that, again, can collapse and incumbent. And that explains why Amazon, which is where this happens, is a, you know, is a fantastic example of, of, of a disruptor. So speaking of Amazon, is customer centricity just a mission statement?

So Amazon has this lovely, uh, you know, mission statement that they have on their website, which is to be the earth’s most customer centric company where customers can find and discover anything they want. And they are customer, you know, generally a customer obsessed company. So they use the word customer a lot of times, but is that just plus? Is that just, you know, something that people say to feel good about themselves? And the answer to that is no, actually, customer centricity is also a part of strategy.

Um, customer centricity in technical terms is a self-organizing community. And so how do you form a self-organizing community? Do you put up forums? Yeah, I mean, sure, you could have some practical way of having it on your app, having it on your platform, so on, so forth. But the idea is that, A, they should be self-organizing, and b, you are not pleasing everyone. You’re pleasing the ones who matter, and the ones who matter are the ones who bring in other people over.

They are advocates of your, of your brand, and that is how you keep the community happy and nourished and thriving. So let’s talk a bit about, uh, moving away. So we’ve talked about the life and death of companies and that large companies die and have been dying very quickly lately. Then we’ve talked about disruption. We’ve talked about how, uh, the new disruptors do things differently, um, over and above the traditional definition of it, which was an algorithmic approach, dramatic simplicity, and building a thriving community.

Then we are going to talk a little bit about moving from products to platforms and to ecosystems. So the original form of, uh, business since the, uh, since we’ve been able to record history, has been about selling products, right? So a product could be a bar of chocolate, like Mars over here. You could have a Volkswagen Beetle, or you could have a film.

A film is a product as well. Um, and so in order to define what a product is, it’s important to, to be able to clearly put some checks on it. So product is a good, or a service that is consumed by a user in almost all of its entirety, usually by paying some price for it upfront. So it’s usually a single revenue stream. Sometimes it could be more, it could be a car plus, you know, it could be some services you get with it.

But the big thing about, um, products are that they do not connect consumers to the suppliers, uh, that constitute the product. So for example, when you go and buy a car from Volkswagen, you do not interact with the, with the company that has put the tires on, on the car, for example. Um, and as a result, there is also no direct feedback loop. You could have some market research like surveys and so on so forth, but there is no direct feedback loop, which happens very quickly that otherwise happens on platforms.

So this is what, uh, you know, at a very broad level is, is what a product is. It’s a very simple transaction. So what are platforms? So platforms are basically, um, platforms are basically not products, but they are, um, a place where users and suppliers are able to connect together and they’re able to generate feedback loops.

These are the feedback loops, right? The yellow and the blues. The more these feedback loops exists, the stronger the platform is. That means if you have more users, you will have more suppliers. If you have more suppliers, you will have more users. And this is known as network effects and very much simplifying this. There’s a lot of math that goes behind it, but in a nutshell, this is what it’s, um, and both of these sites feed to each other.

It’s almost like an infinite loop. Of course, you need to get to a critical mass of both users and suppliers, uh, until the network effects kick in. And, you know, there are different strategies for that, and we can discuss that in the q and a, uh, but this is how platforms work. But the question is, is, is platforms just a thing of the internet? And the answer to that is not actually, uh, platforms have been around, but in non-digital forms.

So you have auction houses, platforms, you know the link, uh, artists to buyers. You have Sunday markets, you know, you go to London, there are Sunday markets, you go and buy, buy food from there, or whatever else you feel like buying. And even universities, this is, uh, King’s College at Cambridge and universities are great platforms as well, because, uh, they bring academics to students, right? So not a new concept, only it has been digitized and it is now running at very, very low cost and at speeds that we could not really think of back in the day.

So multi-site platforms, this is the framework for the strategy that you need to think about when you’re thinking about multi-site platforms. So if you have a startup that wants to be a platform that connects users with suppliers, uh, and also generate network effects, these are the four things you need to think about.

And I can, obviously, there are any specific questions, I will answer them as part of the q and a if we have the time. But it is first is number of sites. There should at least be two of them. Uh, there are a lot of other platforms that have more than two. So for example, LinkedIn has recruiters, advertisers, and people looking for jobs. But it is actually difficult to have a balancing act when you have more than two. So if you are a startup, I would say start off with two and until, unless that gets stabilized, do not be more adventurous and add six more sides because that’s the fastest way to die.

Then designing quality does matter. Although features and quality, uh, are not, uh, do not completely stop a user from switching, they definitely produce, uh, a lot of friction in the process. So make sure that if you are going against some competitor of yours on some dimension, you are better off in terms of design quality. Then there is pricing.

Pricing is not straightforward for platforms. You usually discount one side, uh, or make it free, and you charge another side for the privilege of it, right? So for example, um, in the case of Amazon or eBay, they charge transaction fees to the sellers. They do not charge transaction fees to the users because the profits are being captured by the suppliers, so they know that they can afford it. But if you start charging the users for it, you know, you end up being in a, in a place where, uh, when not many of them will come in because prices would’ve risen for them.