Advisory shares: How much equity should you give your advisor?

Startups commonly give 1% equity to General Advisors paid only in equity, who work less than 2 days a month. Discover m...

If you’ve been sent a Shareholders Agreement and Articles for a funding round, you’ll have seen that collectively they run to 100+ pages of legalese. At SeedLegals our goal is to demystify that and to provide all parties with clarity and transparency to the underlying deal terms.

We’re also uniquely positioned to use deal data gathered over hundreds of rounds done on SeedLegals to not just explain deal terms, but show what’s market standard, and what’s most suitable for your round. As soon as founders and investors can see what’s typical for that type of round and that class of investors, it becomes dramatically faster and easier to agree deal terms.

Having examined hundreds of UK funding rounds, it’s apparent that despite the 100+ pages of legals, most of the negotiation energy goes into just a few key deal terms:

1. Company valuation and amount being raised (obviously)

2. Founder share vesting (investors often insist on founder vesting provisions)

3. Investor Consent

4. Directors and board approvals (investors often want a board position, more on that here)

5. Warranties limits (company and founder liability for any misrepresentations made)

Investor consent rights give investors a say in certain high-level company decisions and are therefore unsurprisingly one of the most hotly negotiated items in a funding round. For founders, they can represent a loss of autonomy in making decisions for the company that they’ve poured their heart and soul into. For investors, consent rights offer an important way to safeguard their investment from potentially costly decisions that, without such consent rights, could be made by the founders without any consultation.

In this article we’ll focus on Investor Consent, explain what it is, show how often it’s granted in different size rounds, and offer suggestions and tactics for your round.

In early stage funding rounds the founders usually own 75%+ of the shares after the round, which means that for anything which requires a shareholder vote, the founders can control the outcome themselves, with the investors powerless to change that, they simply don’t have enough votes. If the founders want to close the company, sell the company, issue more shares, whatever, if they have 75% (or in some cases 50%) or more of the shares, they can just go ahead, pass a Shareholder Resolution, and do it.

For investors, that’s a serious problem because it means the founders can do things which dilute the investors, or invalidate their SEIS or EIS tax relief, or enter into contracts which may benefit the founders but ruin the value of the investors’ investments.

And so the concept of Investor Consent has evolved – it’s an additional right that requires the approval of the investors (typically defined as all shareholders other than the founders) for a range of key company decisions that could affect the value of the investors’ investments. Investor Consent Rights form part of the overall company governance.

We’ve realised that Investor Consent rights can be grouped into three categories, which we’ve optimised over hundreds of rounds:

1. No investor consents

2. Lite consents

3. Full consents

No consent means that the Shareholders Agreement leaves out all mention of investor consents, there aren’t any.

Lite consents provide wording in the Shareholders Agreement specifying that investor consent is needed for a small range of key company decisions which would dramatically affect the value of the investors’ investments:

· Winding up the company or placing it into administration

· Creating or redeeming any share or loan capital

· Doing an IPO

· Changing the company’s Articles (which could be done to e.g. change share class rights)

Full consents go a step further, requiring investor consent for a range of things that the company may occasionally need to do:

· Change its share capital or the rights of its shares

· Change its accounting date

· Change the company name

· Sell any part of the company

· Assign or transfer any of the company’s intellectual property rights

· Enter into a joint venture or create a subsidiary

· Pay a dividend

· Pay any bonuses or commission payments

Grouping the consents in this way, based on deal data, and providing founders with a one-click option to pick the one that’s right for them and their investors helps close rounds faster and more efficiently, and steers everyone to standard set of terms that not just help the company operate efficiently on a day-to-day basis, but will assure future investors that the company has been set up and is governed sensibly and with a care to investors’ interests.

Investor consent rights are an important way for investors to safeguard their investment from potentially costly mistakes while enabling them to leverage their experience to make a meaningful contribution to the company. However, if the list of items requiring consent is overly vague, broad, or onerous that can lead to problems down the line with the possibility for investor disagreement over what was meant, or conversely negatively impact founder’s productivity by causing delays or blocking of key company decisions. Grouping and packaging those consent rights has proven invaluable in helping founders and investors reach agreement on these points quickly and efficiently.

So, here’s what’s being agreed across hundreds of UK angel and seed rounds closed on SeedLegals – we hope it helps you decide what’s right for your company and your investors.

Overall, 68% of funding rounds closed on SeedLegals include investor consent rights.

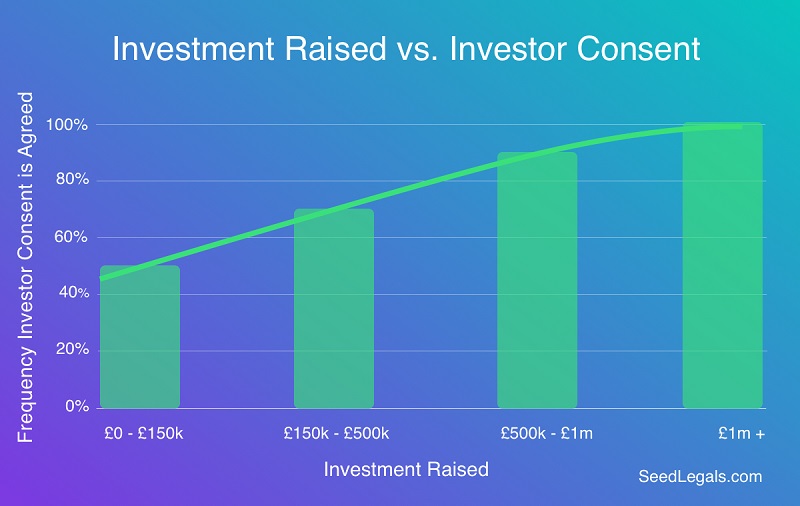

Our data also shows that the likelihood of investor consent being specified varies with the size of the funding round:

· Rounds under £150k have investor consent about half the time

· Rounds over £1m will rarely be without investor consent.

Typically in smaller rounds of £150k or so, a large portion of the funds come from friends, family and the founder’s professional network. These investors are early champions of the concept and will often have limited experience investing in startups. They’ll therefore be less likely to demand investor consent rights. And with so much of the business’s strategy and future direction still being crystalised, the inclusion of investor consent rights at this early stage can prove to be a cumbersome extra layer.

As round sizes increase, the number of professional investors rises, with professional angel investors typically present in rounds of £150k – £1m, and corporate investors, funds and VCs starting to enter at around the £500K round size mark. Since venture capital firms have a fiduciary responsibility to their LPs (the investors in their fund), it would be extremely rare to see a funding round with a VC investor that doesn’t include investor consent rights.

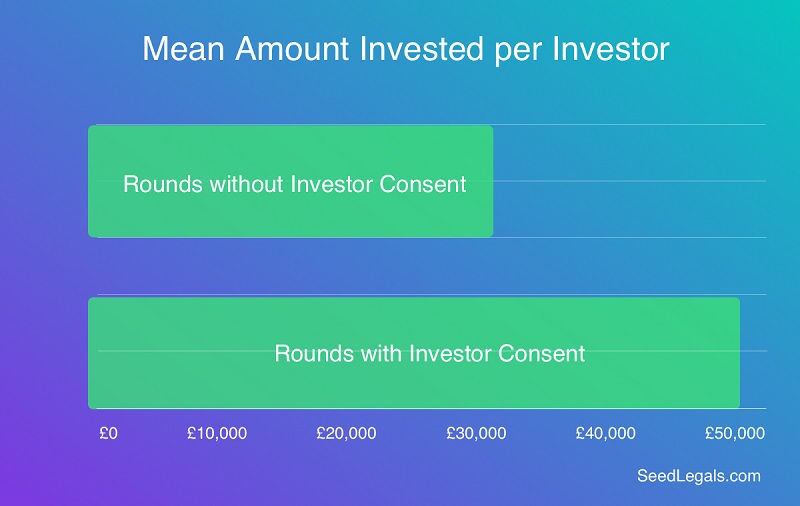

Apart from the size of the round, the amount invested per each investor plays a role in determining the likelihood that investor consent will be present since investors’ incentive to protect their investment increases with the amount of their capital at risk:

As one would expect, we found the average amount invested per investor to be higher in rounds containing investor consent.

The extreme example of this would be a crowdfunding round with hundreds of investors investing between £100 and £20K. In those cases not only is there typically no investor consent at all, but the minor shareholders don’t even get voting shares (trying to round up 500 investors each time an investor consent is needed would be crazy) – something that investors investing in a crowd round should be aware of.

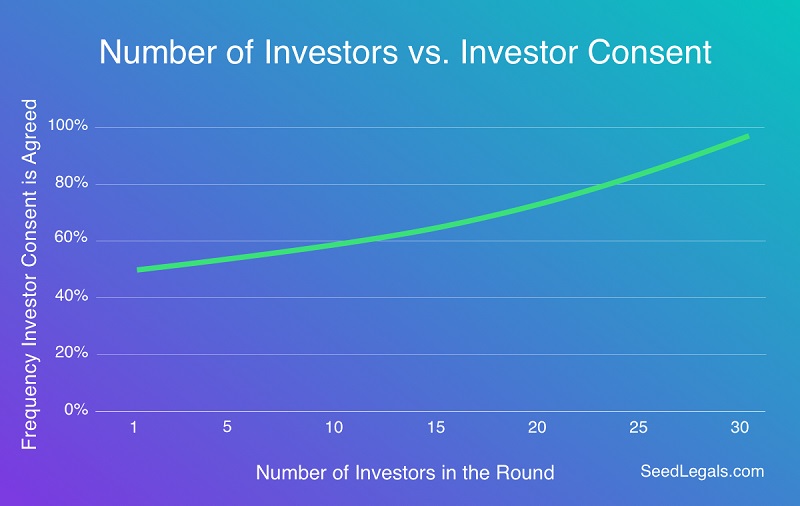

We also found that the number of investors in a round correlated positively with the prevalence of investor consent rights:

The data suggests that a higher number of investors in a round increases the likelihood that at least one investor will demand an investor consent right, which then typically applies to all the investors in that round.

But, once you get to crowdfunding levels of investors (e.g. hundreds of investors), the investor consent right either disappears or is restricted to just a few of the larger investors, obviously because it’s just too much trouble to round up hundreds of minor investors for each consent matter.

When a startup does its first funding round it’s obvious who the investors are – they are the people investing money in the business, basically anyone who has paid for their shares (as opposed to founders and employees who got shares essentially for free when the company was formed).

Now imagine the following scenario:

Assuming that the investors in the January round got investor consent rights, what should happen in the October round?

1. The investor consent rights are now given to the October investors (the consent rights go to the “New Investors”), and the January investors lose their investor consent rights, or

2. The investor consent rights are given to the October investors, but the January investors keep their investor consent rights (the consent rights go to the “New and Existing Investors”)

So, which should apply to your round?

Broadly:

If your new round is much larger than the previous one, and you’re transitioning from angel investors to VCs and funds, then usually the VCs and funds will demand that only the New Investors in the new round will get investor consent rights, and the earlier angel investors will lose their investor consent rights. Which is not unreasonable if the new investors are investing several times what the original investors invested.

Or, if the new round isn’t substantially larger, and you have largely the same types of investors as before – e.g. more angels – then you would keep everyone happy by assigning the investor consent rights to the New and Existing Investors.

But, sometimes it’s not about new vs. existing investors, you just want to give investor consent rights to a particular set of investors. For example, if you have a bunch of investors putting in £10K each and a few putting in £200K each, you can give the smaller investors Ordinary shares, and the larger investors, say, A Ordinary shares. Then, you can do clever things like giving investor consent rights to “the holders of A Ordinary shares”.

SeedLegals takes this complex and important set of options and packages them up in a way that lets you easily decide what’s right for the company and the investors, and then specify that in a few clicks.

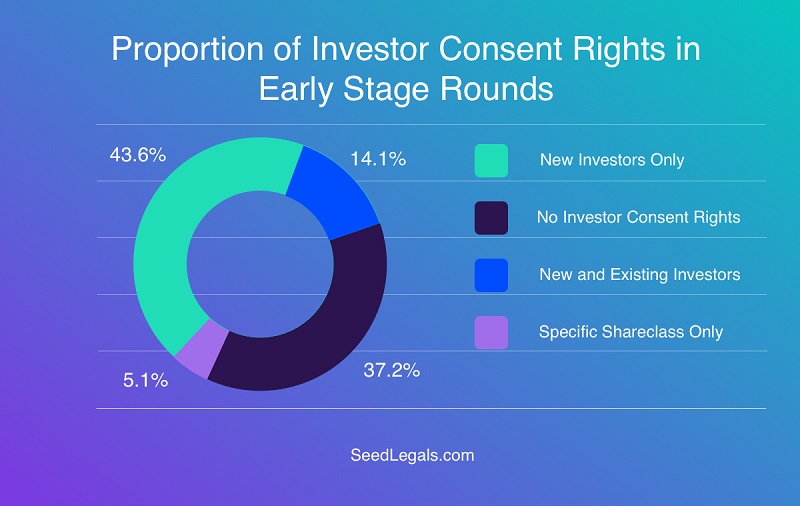

The data shows that most of the time the investor consent rights go to the New Investors. That’s not so surprising, as there are more first rounds than second rounds, not everyone makes it to (or needs) a second or more funding rounds.

Giving investor consent to specific share classes serves a specialist need and is used infrequently – but when you have that need, it’s a fantastic and easy to set up solution.

If you’re a founder who is creating a Term Sheet to send to potential investors (SeedLegals changes everything, you no longer need to have investors send you their Term Sheet, finally you can lead on this yourself), what should your strategy be on offering Investor Consent rights?

Here’s our suggestion:

1. If you’re doing a small friends and family round using our Bootstrap Round package, don’t worry about this – our Bootstrap Round is perfectly tuned for that type of round and doesn’t include investor consent provisions at all.

2. If you’re doing a £150K to £300K SEIS/EIS round, with mostly people you know and friendly angel investors, you might want to lead with no investor consent, and only change that if your investors ask for it.

3. If you’re doing a £300K to £700K round with professional angel investors, offering no investor consents is likely to get a sniffy response, they may think you’re trying your luck with them. So you might select Lite consents, which means you’ll only ever need investor consent for a new funding round or something goes very wrong with the company.

4. If you’re doing a £500K+ round with fund or VC investors, you might be tempted to start by offering Lite consents, but don’t be surprised if you get back an email listing a long set of consent rights the investor is looking for. The list they will send you is likely to be longer and more onerous than the Full set we provide in SeedLegals (and yet offer little or no real added value), so if you think your investors are going to expect the full set then you’re best off offering that in the first place.

We’re here to help you every step of the way, both with data-driven insights like this, and with personalised help from our expert team. Want to know more? Just hit the chat button (bottom right of your screen) or book a free call with one of our specialists.